Attendance at religious services and the subjective importance attached to religion are declining in virtually every advanced industrial society. But in the world as a whole, a larger number of people hold strong religious beliefs than ever before.

These are some of the findings in “Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide” by ISR research scientist Ronald Inglehart, who directs the World Values Surveys, and Harvard political scientist Pippa Norris. The book will be published in October by Cambridge University Press.

In the book, Inglehart and Norris explore the reasons behind the enduring vitality of religion in the modern world. They look at the continued popularity of church-going in the United States and the emergence of New Age spirituality in Western Europe. They study the surge of fundamentalist Islam in the Muslim world, the evangelical revival sweeping through Latin America and the intractability of widespread ethno-religious conflicts around the world.

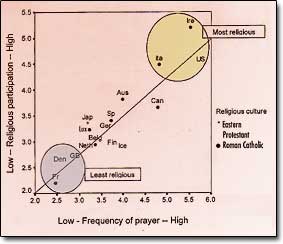

Inglehart and Norris show that although members of virtually all advanced industrial societies have been moving toward more secular orientations during the past 50 years, people with traditional religious views constitute a growing proportion of the world’s population.

Secularization is occurring in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Canada and Western Europe, new data from the World Values Surveys shows.

“Even in the U.S., there has been some movement in this direction, although this trend has been partly masked by massive immigration of people with relatively traditional worldviews, and high fertility rates, from Hispanic countries,” Inglehart says.

Within most advanced industrial societies, attendance at religious services has fallen during the past several decades, Inglehart notes. Religious authorities largely have lost their authority to dictate to the public on birth control, divorce, abortion, sexual orientation and the necessity of marriage before childbirth.

But this process of secularization is linked with a sharp decline in human fertility rates: Women in advanced industrial societies, on average, have as few as 1.2 children during their lifetime—while women in low-income countries, which tend to be much more religious, have as many as five or six children. As a result, the proportion of the world’s population with traditional religious values is growing, not shrinking.

But even in advanced industrial societies, Inglehart emphasizes, evidence from the World Values Surveys indicates that a growing percentage of the public spends time thinking about the meaning and purpose of life. “Organized religion is losing its grip on the public, but spiritual concerns, broadly defined, are taking on growing importance.”

The book also presents intriguing, counterintuitive findings about the relationship between specific religions and political and social worldviews. For example, 64 percent of the Buddhists in the worldwide sample say they lean to the right politically. By comparison, almost half (48 percent) of Hindus and Protestants say their political views lean to the right, followed by 47 percent of Catholics, 46 percent of Muslims, 41 percent of Jews, 38 percent of Orthodox Christians and 36 percent of those with no religious affiliation.

The findings also show that Moslems are much more likely than Protestants to subscribe to the values associated with the Protestant work ethic.

“Protestants today display the weakest work ethic of any of the major religious denominations,” Inglehart says. “An important reason is that Protestants are likely to live in rich nations, where people place the greatest importance on leisure, relaxation and self-fulfillment outside of work. In poorer developing nations, where Moslems are likely to live, work is essential for life and people place a high emphasis on its value.”