The University Record, June 7, 1999 By Rebecca A. Doyle

Everyone in the world can do something you can’t do, and that thing is becoming more and more a part of your educational, work and everyday environment.

For the visually impaired, that thing is surfing the Web in search of its increasingly abundant sources of information. As more and more Web sites have been developed at the U-M, and become the method of choice for distribution of information, some visually impaired students find that even the syllabi necessary for their courses are not available without either special tools or special individual assistance.

Several specific problems face the visually impaired student or employee at the U-M who tries to find information in the growing Web repository. According to a study of the problem prepared by graduate students in the School of Information, none of 65 U-M academic and service sites chosen passed an accessibility test that would make it possible for visually impaired people to access the information they need.

In April, Mary Carleton, Pam Chamberlain, Hans Masing and Ann Sinfield presented the report and met with campus Web designers to discuss their findings. “That was one of the most quiet meetings of this group I have ever seen,” Masing says.

No one deliberately tries to prevent or make access to Web pages more difficult—the object of the Internet and the Web is, after all, making information more accessible. But Web designers had simply not considered accessibility for visually impaired users. Masing, who also is employed by the Information Technology Division, has posted guidelines on accessible Web design on his personal site, http://www-personal.umich.edu/~hmasing/webguide/.

In evaluating the pervasiveness of the Web at the U-M, the team estimated that 18,300 sites are hosted on U-M servers. While most of those are personal home pages of faculty, staff and students, a significant number contain “essential information for students, faculty and staff,” noted the team in the report. “Most importantly, on many of these sites, the Web is the only place that the information is available.”

While that works well for most people, those with visual disabilities rely on software that can translate printed text into spoken words. Screen readers commonly do not recognize column format, or text in tables on Web pages. Therefore, what may be perfectly discernible to sighted Web browsers as two separate items may be read to a blind user as one. For example:

|

Classes will begin June 21 |

For more information |

|

at the Pierpont Commons |

visit our site |

|

lower level. |

on the Web at |

|

http://www.umich.edu/ |

|

|

moreinfo. |

A screen reader would read this material as “For more information, Classes will begin June 21 visit our site at the Pierpont Commons on the Web at lower level. www.umich.edu/moreinfo.‘ target=’_parent’>http://www.umich.edu/moreinfo.;

The report also cited as problematic for screen readers frames without titles, server-side-only image maps and, the number one complaint, the growing number of graphic images on pages without any accompanying text or informative title. The last item also reflects one of the biggest reasons that those who have older computers may leave a Web site that relies on graphics to provide information and is meaningless in text-only mode.

Masing notes that providing access to information is not something the University can decide to do or not to do. The University, as a public institution, is bound under the Americans with Disabilities Act to provide not only physical access to the University, but equal access to information.

“This is something we have known for some time we needed to address,” notes Sam Goodin, associate dean of students, special services, in the Office of Services for Students with Disabilities (OSSD). But Goodin notes that the task seemed huge and says his office was “intimidated by the size of the project.” When the School of Information students approached them, Goodin says they were happy to have the project in the students’ competent hands. The OSSD is looking into moving the project report and guidelines for accessible Web page design into IFS space under OSSD during the summer.

Commitment to helping visually impaired leads to award for U-M staff member

By Rebecca A. Doyle

During the day, David Erdody works as an academic services clerk in the Office of Financial Aid.

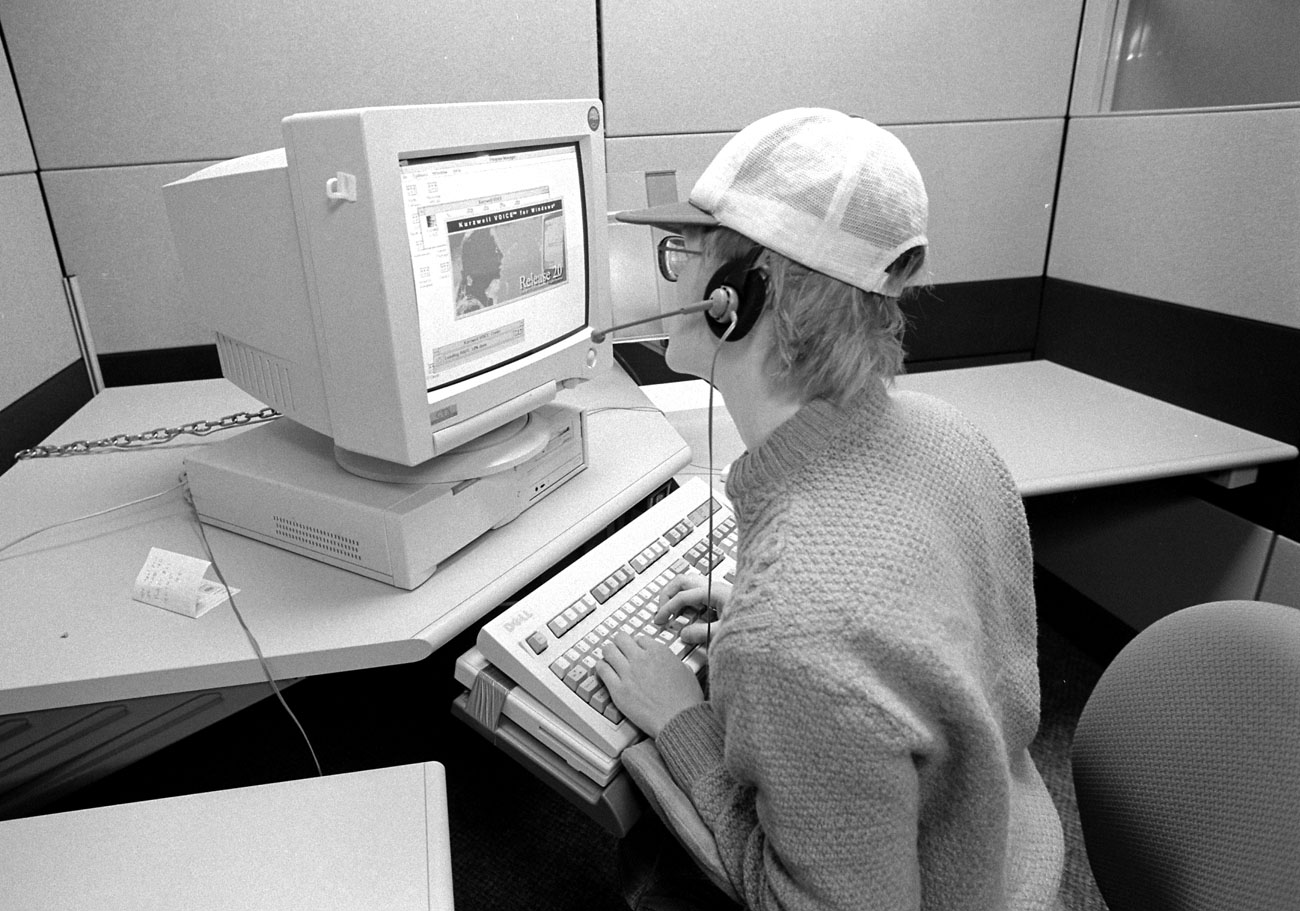

But when adding information to his Web site for those who can9t see visual images well or who prefer hearing the words.

Erdody spends his nights and weekends hunched over a computer keyboard or, with a small corps of volunteers, reading current magazine articles into a microphone. Then, using RealAudio and his personally financed Web site, he makes the articles accessible for those with visual impairments who can9t get the information in any other way.

Erdody recently accepted the 1999 Streamers Progressive Award, presented by RealNetworks and sponsored by the Intel Corp., for Assistive Media, his non-profit site.

While he is quick to point out that volunteers read much of the material he makes available, visitors to the site can always find his name listed as one of the readers of the several magazine articles chosen to appear on the site.

‘I just come across information that is interesting to me and pass it on to someone who couldn9t reach it otherwise,2 he says. That is the incentive that drives his after-hours labor, coupled with the sense of need he felt when he learned how little is available to those who can9t read printed matter.

Erdody says he used to listen to audio tapes of books during his commute to classes, and started paying attention to the scarcity of materials available on cassette when he learned that his father, who is diabetic, might someday lose his sight.

‘I was told by one librarian that only 3 percent of the published books in the United States are made into an alternative format for the handicapped,2 he says. Erdody was determined to increase the audio holdings that are available and initially began to read and distribute audio tapes of magazine articles.

Then he discovered that Internet technology and RealAudio9s availability could be combined to offer the reading to a much larger audience. He currently logs 15,000 visits to his site each month.

‘What I would like to do is set this up like public television where I can offer the service for free without commercials and have it funded by the private sector,2 Erdody notes. He has received some funding from the Lions Club in Ann Arbor and a computer from Apple, but still relies on volunteers for reading and does the rest of the work himself.

To visit the Assistive Media site, set your browser to http://www.assistivemedia.org. If you do not have a copy of RealAudio, it is available for download from the site without cost.