The University Record, April 5, 1999

By Nancy Ross Flanigan

News and Information Services

Drilling, filling, bonding, bleaching–if that’s your idea of dentistry, it’s time to take a closer look. Dental researchers today are as likely to study genes as gingivitis, and rather than focusing just on teeth, they’re turning their attention to structures of the whole head and face. Of course, cavities and cosmetic dentistry still get a fair amount of attention, too. This whole spectrum of dental research trends is reflected in presentations researchers from the University of Michigan School of Dentistry made at the annual meeting of the International Association of Dental Research in Vancouver, British Columbia, March 10-13. Here are details on a few topics:

Fixing faces and fractures

Facial deformities, fractures that won’t heal–these serious medical problems usually require surgery and extensive bone grafts. Imagine how much simpler it would be to treat these problems with genes that help build bones. Renny Franceschi, associate professor of dentistry, and Bruce Rutherford, professor of dentistry, are in the early stages of research aimed at reaching that goal.

One of the first steps is to find ways of delivering the proper genes into the body and getting them to work as they should. Franceschi and Rutherford are working with genes for bone morphogenetic proteins, which induce bone formation. In recent animal experiments, they showed it was possible to use a standard gene delivery method–a virus modified to be harmless–to get bone morphogenetic protein genes into the body. Once inside, the genes functioned normally to induce bone formation.

Next, the researchers plan to fine-tune the system to make it work as efficiently as possible. Once this is accomplished, the next step will be to use the gene delivery system to try to repair fractures and skull deformities in animals.

Fluoride freeze

It’s in our toothpaste, in our water, and in the gels that dentists swab on our teeth. In the United States, getting enough fluoride isn’t a problem, but getting too much may be. While there’s no evidence that too much fluoride causes serious health problems, it can cause a condition called fluorosis, says Brian Burt, a professor of dental public health and adjunct professor of dentistry. In the mild form most often seen in this country, fluorosis causes faint white splotches on the teeth. In parts of the world where natural fluoride levels are high, fluorosis can lead to heavy staining and the breakdown of tooth enamel.

Fluorosis occurs when children ingest too much fluoride as their teeth are developing–during the first seven years of life. Knowing exactly when during that period children are most vulnerable could help dentists develop strategies for preventing the problem. To pinpoint that period, Burt and colleagues at the U-M and Duke University Medical Center studied what happened when equipment problems forced the city of Durham, N.C., to stop adding fluoride to its water supply for 11 months. The fluoride break was not publicized, so dentists and patients didn’t increase their use of fluoride products to compensate.

Burt’s group found that while the fluoride break did not lead to an increase in tooth decay–probably because children were still getting plenty of fluoride from toothpaste and dental office applications–it did markedly reduce the incidence of fluorosis. The greatest effect was seen in children who were between 1 and 3 when the fluoride break occurred.

This suggests that parents should be especially careful about how much fluoride toddlers swallow, says Burt.

Drinking fluoridated water should not cause problems as long as the amount of fluoride from other sources is not too high, he says. Parents should teach small children to use only a small amount of toothpaste and not to swallow mouthfuls of froth. Dental office fluoride treatments are good for those children who still are susceptible to tooth decay, but they don’t add much anti-decay protection for children with few or no cavities.

Parents whose dentists or pediatricians prescribe fluoride tablets or drops for their small children should be aware that there is a risk of mild fluorosis to be balanced against any benefit from the fluoride. And fluoride tablets or drops should never be taken by children who also drink fluoridated water.

A soft spot for babies

That soft little spot at the top of a baby’s head may seem like the height of vulnerability, but it serves an important purpose. Normally, the bony plates that make up the top of the skull don’t begin to fuse until around age 2, allowing plenty of room for the child’s developing brain. But in about one of every 3,000 children born, one or more plates fuse too soon, and the skull becomes deformed.

To correct the problem and give the child’s brain room to grow, doctors must remove the top of the skull, cut it into pieces with a surgical saw, then put the pieces back into place with tiny screws and metal plates. Researchers in the lab of Prof. Michael A. Ignelzi Jr., assistant professor of dentistry, are trying to understand why premature fusion, called craniosynostosis, occurs, with the eventual goal of finding ways of preventing the problem.

Senior dental student Rebecca Ainge investigated the role of the brain’s covering, called the dura mater, in craniosynostosis. In experiments with mice, Ainge found evidence that the dura mater secretes chemical messengers that keep the plates from fusing too soon. Studies by other researchers have linked certain genetic mutations to craniosynostosis.

Ignelzi, Ainge and their coworkers would like to know exactly how these genes and their products interact with the chemical messengers secreted by the dura mater. This knowledge may someday lead to gene therapy strategies for preventing the skull bones from fusing too early.

Smile for the camera

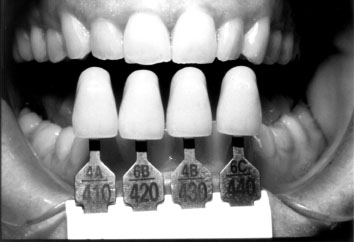

Porcelain crowns and veneers can significantly improve the appearance of imperfect teeth. But the effect often is ruined by less-than-perfect color matches. The problem, says William J. O’Brien, director of the Biomaterials Research Center, is that dentists haven’t had accurate, objective ways to measure the color of existing teeth. The standard method is to visually compare a patient’s teeth to a set of 16 color samples, “which are shaped like teeth, but are otherwise like paint store chips,” O’Brien says. Sometimes dentists get the color right, but often they don’t. In studies, their average success rate is only 45 to 50 percent. In other products where color matches are important–house paint and automobile finishes, for example–technicians use an instrument called a colorimeter to objectively characterize colors. But colorimeters work best on flat, opaque, featureless objects. They don’t do well with teeth, which are translucent and three-dimensional.

O’Brien’s research group has developed a simple method, with funding from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, called photocolorimetry that allows for much closer matches between natural teeth and restorative work. Instead of directly measuring tooth color with a colorimeter, teeth are photographed in natural light and the colorimeter is used to measure tooth color on the photograph. Because even the best photographic methods distort colors slightly, the researchers developed a set of computational steps that corrects such distortions.

The result is a truer measure of tooth color. Compared to the 45-50 percent success rate of visual matching, photocolorimetry is 80-90 percent successful in matching tooth colors, O’Brien says. The more accurate matching technique should translate into savings for patients, because dental laboratories won’t have to remake crowns to get them to match. Patients won’t spend as much time in the dentist’s chair, either, if the crown matches on the first try.

Bad breath bugs?

Is bad breath the work of bad bugs? That’s what research fellow Christopher Kazor is trying to find out. With help from dental student Jamal Flowers, Kazor is studying the bacterial population that normally lives on the tongue. He then wants to compare this normal assemblage with bacteria found on the tongues of people with bad breath.

Surprisingly, some 80 percent of the bacteria in the normal mouth have never been identified, says Kazor, so that’s the first step. Once that’s done, Kazor will use similar methods to characterize the bacterial population on tongues of people with bad breath. By identifying differences in the quantity and type of bacteria from these groups, Kazor says it will be possible to better treat bad breath by specifically targeting the bad-breath bugs.

The subject is saliva

Ever stop to think about how many times you lick your lips in one day? Mouth moisture is something most people take for granted. But many prescription and over-the-counter drugs cause dry mouth, which may lead to cavities and oral infections and to problems with talking, chewing, swallowing, tasting and retaining dentures.

Dry mouth is a particular problem for older people, but not because their salivary glands don’t work as well as those of younger people. The real reason, researchers have suspected, is that older people are more sensitive to the effects of mouth-drying medications.

A research team led by Jonathan Ship, an associate professor of dentistry, now has tested that notion and found it to be true. When healthy adults in two age groups (ages 20-40 and ages 60-80) were given a mouth-drying drug, its effects showed up sooner and were more pronounced in the older group. If mouth-drying drugs must be prescribed, patients and their dentists should take extra care to prevent related oral health problems.

In other work, Ship’s team found that people with poorly-controlled diabetes have drier mouths than either people without diabetes or people with well-controlled diabetes. However, for reasons that aren’t understood, these people don’t complain of mouth dryness. These findings underscore the importance of controlling diabetes and of dentists paying special attention to the oral health of diabetic patients.