The University Record, June 24, 1998

U centers play vital role in early childhood development

By Rebecca A. Doyle

The University’s five child care centers all operate differently–some offer full-time care, some take younger children and they close for different days during the year.

The University’s five child care centers all operate differently–some offer full-time care, some take younger children and they close for different days during the year.

But they have one important thing in common–they are among only 10 percent of the early education programs that are nationally accredited. Helping children learn and grow in the best environment and in the best direction for each child is the monumental task they face eagerly each day.

Recently published research has shown that early childhood education is vital to later development for children in school and beyond. Teachers in the University’s facilities take their role seriously in preparing children for school and for life by making sure they are exposed to learning in an environment that is supportive and offers variety and encouragement.

A typical day for the U-M’s teachers and assistants includes not only a day filled with activities designed for very young children with short attention spans, but a growing need on part of the parents for interaction with the teacher.

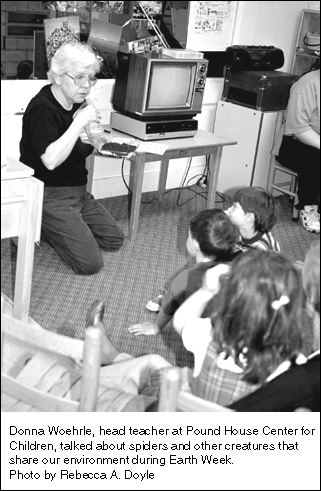

“Early childhood teachers play a unique role,” notes Donna Woehrle, head teacher at Pound House Children’s Center. “Families are isolated now from extended family and we have become their support system. We know the children as people, and often act as peers for parents who are, especially here at the U-M, sometimes older and have no peers with children the same age.”

Woehrle’s day technically begins when she opens the doors and prepares to greet the children and parents as they come in to the Forest Avenue facility. Then comes activity time, reading time, outdoor time, potty time, lunchtime, rest time, more activity time and preparing to go home. But even before that she is planning and thinking about the day’s lessons. Because there is little time to search for materials or plan lessons, Woehrle says her job also goes home with her, as it does for most early childhood teachers.

“We are constantly going, observing, acting as models for the student assistants in the classroom,” agrees Rita Friedman.

Friedman and Woehrle spend hours outside the center searching for supplies for crafts, thinking about new ways to stimulate children and going over lesson plans. Despite schedules that allow no room for sitting down and putting up your feet, the two are happy to be working with children.

Friedman and Woehrle spend hours outside the center searching for supplies for crafts, thinking about new ways to stimulate children and going over lesson plans. Despite schedules that allow no room for sitting down and putting up your feet, the two are happy to be working with children.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of learning from children and being with them. Growing up is a complex area and it has been extremely satisfying observing the children do all the things I have read about and learned,” Woehrle says. “It is a constant challenge, and in all these years I have never figured it all out.”

Every day there is something new for child care providers to learn from their charges as much as there is something for the children to learn from teachers and caregivers.

“As teachers, we become a part of the way they feel about the learning environment, ” Friedman says. “Just think–we could be making widgets, but instead we’re growing people.” That, says Pound House Director Carolyn Tyson, is what attracts many University students who come to Pound House for Children as volunteers or interns.

But even though they show great promise as educators and as much as they may love being with children in a learning environment, few of them plan to make it a career. Tyson says it is rare that anyone stays in a preschool teaching position for more than a few years because of the low pay and because of incentives offered in the public school system.

“Public schools offer higher salaries than many of the centers can provide, and there is just not the commitment to early childhood education that there is to public school funding,” she notes. While preschool teachers at the U-M are paid better than most, many of them have been “lured away” by the public school system, which pays about 70 percent more than the centers can at the beginning levels.

Although research has shown that the years 0-8 are the time in life when brain development and learning are the most crucial, the history of women staying home with children combined with the perception of early childhood education as babysitting have kept wages low in the field.

Friedman, who has worked with children for more than 20 years; Woehrle, who has been in the field for 18 years; and Tyson all agree that it will not be long before there is a real shortage of qualified early childhood teachers, and that very young children who may be exposed to a fast rotation of teachers will be emotionally hurt when they feel abandoned by a teacher.

However, Tyson says, “Although we are deeply concerned about the future, our primary focus is providing for the needs of the children now. Quality care does make a difference in the lives of young children, and we continue to do all we can for those entrusted to our care.”

Early childhood education centers on the Ann Arbor campus

• The Children’s Center, part-time, ages 18 months-5 years, 763-6784.

• The Children’s Center for Working Families, full time, ages 2-1/2-5 years, 998-7600.

• Pound House Children’s Center, part and full time, 998-8440.

• Family Housing Child Development Center, full time and part time, ages 2-1/2-5 years, 764-4557.

• University Hospitals Child Care Center, full time and part time, ages 2 weeks-5 years, 998-6195.

All centers are accredited by the National Academy of Early Childhood Programs.