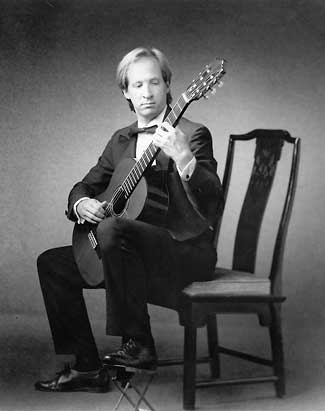

Joseph Pratt preserves books for a living but he lives to play music.

“When I was learning classical guitar I would hear the voice of angels,” says Pratt, who pursued nearly three years of formal studies to discover how to coax a heavenly sound from the guitar.

As an information resource assistant in the Preservation Department, he helps keep books from falling apart. Pratt examines books in every library except the Law Library and the Kresge Business Library. For 11 years, Pratt has managed the day-to-day operations of the mass deacidification program. Treating books that were bound with acidic paper is a part of insuring their longevity, because paper that is acidic will fall apart over time.

Deacidification involves a process in which fanned open books are dipped in a fluid suspension of a buffer in powder form that can be likened to a dry cleaning fluid. Pages don’t get wet, as an alkaline powder coats them. “This serves to neutralize the acid in the paper,” Pratt says.

He tests some 100 books per week. Using a chlorophenol red pH indicator dye pen, a mark is made on paper on the bottom of the book. The appearance of the dye in one or another color indicates the presence of acid.

He also is responsible for environmental monitoring. The campus libraries have sensors that record the temperature and humidity of rooms that contain collections. The data is reviewed to determine what adjustments need to be made to achieve the best conditions.

While books demand Pratt’s attention during work hours, the rest of his time is occupied by music. Rock was Pratt’s love when he started playing guitar in 1977.

“I wanted to play the music I was listening to. My influences in the ’70s were Al DeMeola, Carlos Santana, Alex Lifeson of Rush, and Steve Howe of Yes.”

Then a couple of years later, “I heard a recording of Christopher Parkening and another of John Williams. I loved the classical guitar music when I heard it,” he says. “I understood at the time that learning classical guitar technique would give me the ability to more easily play any style that I wished.

“Certainly, the strength and hand positions that I acquired for classical training lent itself well to picking up flamenco guitar later on. Also, my exploration of Brazilian Guitar sounds has been well supported by classical technique.”

Like jazz and blues in the United States, flamenco music in Spain was developed by groups on the fringes of society, Pratt says. “Arabs, Jews, Gypsies and others contributed musical styles from their own histories. These styles were blended and distorted during times of great social and political pressure.”

He says that while purity of sound is important in his development as a classical guitarist, passion is vital for playing flamenco guitar. The Ann Arbor Observer once described Pratt as “technically sophisticated” with an “impressive command of varied musical syntax.” The Ann Arbor News once wrote that Pratt added “biting flamenco guitar” to an Ann Arbor Civic Theater production.

Pratt says Parkening, Williams and Pepe Romero have a quality of tone that he admires. His flamenco influences are Sibicas and Paco Delucia. “When I hear these flamenco players, I’m impressed with the forthrightness of emotion,” he says, adding these musicians are straightforward about whether they’re happy, sad or angry.

While he’s considered trying to make music a full-time occupation, “It would become like a job,” Pratt says. He performs each Friday evening at the Amadeus Restaurant and has completed two recordings on CD: Mediterranean Topology and Mercurial.

Pratt values his co-workers understanding and support of his devotion to music. “There is awareness and appreciation people have for diversity and culture, and encouragement for what people do outside of U-M,” he says.

While Pratt still owns an electric guitar, “I haven’t picked it up in years.”