Cathleen Baker’s devotion to the Beatles is such that she earned the moniker “Beatle” during her undergraduate days at the University.

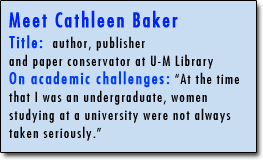

“They were so witty, so intelligent, so British,” Baker says. Just as the Beatles blazed a unique trail in popular music, Cathleen Baker emerged from a theory-centric field to create a distinctive professional niche. She fused her two loves, art and science, into a distinguished career as an author, publisher and paper conservator at U-M Library.

As a U-M sophomore in 1968, Baker struggled with limited curriculum and post-graduate expectations. “At the time that I was an undergraduate, women studying at a university were not always taken seriously,” she says. “They were at these institutions for their ‘Mrs. degrees.’ In the field of art history, especially, women were not generally expected to go on to high-level positions in the art history world or in academia, to become curators and historians.”

Baker was fascinated with the making of art. While on a lecturing internship at the Toledo Museum of Art, she observed the conservation of paintings for the first time.

Ironically, her growing interest with conservation would dovetail with her Beatle infatuation. Deciding she had to live in the group’s native England, Baker moved to London. She took a job at the Courtauld Institute of Art at the University of London, which led to her becoming the paper conservator of the Witt Collection of Old Master Drawings and for the Palladio drawings in the Royal Institute of British Architects.

While working on priceless works of art on paper, however, she began to realize that she knew little about the technical aspects of papermaking, drawing and printmaking. The determination to learn more led to her return to the United States to teach paper conservation in the Cooperstown Graduate Program and the Art Conservation Department, Buffalo State College, for 15 years. Teaching the conservation of predominately American works of art and archival collections “kindled an interest in American art, as well as this country’s papermaking and print mediums, especially in the 19th century,” she says.

In 1990, Baker embarked on a project to write a biography of Dard Hunter, a major designer in the American arts and crafts movement in the early 20th century. His grandson, Dard Hunter III, invited Baker to take up residency at the Hunter home in Chillicote, Ohio. Baker had access to the Hunters’ previously undiscovered personal archives. The resulting “By His Own Labor: The Biography of Dard Hunter,” by Baker, was hand-printed in a limited edition and published in 2000.

While pursuing her master of fine arts in book arts and doctorate in mass communication from the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Baker established her own Legacy Press in 1997. One forthcoming title discusses the relationship between paper and spirituality in Asian cultures.

A few years ago, when she received a grant to write a book on 19th century American paper, Baker contacted Shannon Zachary, head of preservation and conservation at the U-M Library.

Zachary created a unique conservation position for her. Now she works primarily on conserving works of art and other flat paper artifacts, primarily for Special Collections and the Map Library.