The University Record, September 7, 1999 By Joanne Nesbit

News and Information Services

|

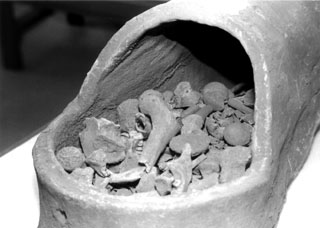

| The Parthian coffin is made of reddish brown clay broken by plaster patches. From above it seems to form an oval pinched at one end to a narrow point. From the side it looks like a slipper with a hole for the lid in the location where the ankle would leave the shoe. Photo by Paul Jaronski, Photo Services |

Unearthed in 1927 during the University’s excavations at Seleucia-on-the-Tigris, about 20 miles south of modern Baghdad, the Parthian slipper coffin went unnoticed in the basement of the Kelsey Museum until summer 1998. It was then, more than 70 years after its initial discovery, that the coffin was discovered again—this time by Will Pestle, a research assistant at the Museum.

Among the stacks of handwritten field notes and diaries left by the original excavators, Pestle had found only a brief mention of a small coffin containing the remains of two infants. Pestle and Museum Registrar Robin Meador-Woodruff, located the coffin looking nothing like they expected. “The coffin’s shape is reminiscent of a ballet slipper,” Pestle says, “narrower at one end than the other, with a hole in the wide end to accommodate the lid.”

When the small circular lid was removed, the coffin revealed a jumble of bones piled along with peanut shells, cotton, straw packing material and pieces of paper with both English and Arabic script. “This was evidence that the contents had been disturbed,” Pestle says.

The mix revealed unburned human skeletal remains that contradicted the field notes. The coffin contained four individuals, none of whom was an infant. Pestle determined that one of the individuals was 12–15 years of age and possibly male, a second 6–8 years of age and of indeterminate sex. Pestle determined the third individual to be 4–6 years of age and of indeterminate sex and the fourth to be an adult male.

Pestle says the coffin lacks any obvious decoration, in contrast to coffins found at other Parthian sites. But under raking light, Pestle did find incised lines on both the lid and the top that formed symbols of an unknown nature. He dates the coffin at about 143 BCE–48CE.

One unanswered question raised by Pestle’s examination of the coffin and its contents is why so many individuals were present in such a small funerary container. “Perhaps the individuals here interred were part of a family group,” Pestle says, “or they may have been siblings.” Still, Pestle speculates, there could have been a reburial of these individuals, or the primary inhabitant of the coffin could have been exposed for the purpose of “defleshing” prior to burial and when the remains returned to the coffin, fragments of other individuals were mistakenly included.

“While all of these are possibilities,” Pestle says, “a definitive answer is almost impossible to formulate.”