New lab-on-a-chip measures mechanics of bacteria colonies

Researchers at U-M have devised a microscale tool to help them understand the mechanical behavior of biofilms, slimy colonies of bacteria involved in most human infectious diseases.

Most bacteria in nature take the form of biofilms. Bacteria are single-celled organisms, but they rarely live alone, says John Younger, associate chair for research in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the U-M Health System. Younger is a co-author of a paper about the research in the July 7 edition of Langmuir.

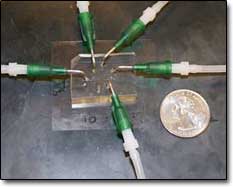

The new tool is a microfluidic device, also known as a “lab-on-a-chip.” Representing a new application of microfluidics, the device measures biofilms’ resistance to pressure. Biofilms experience various kinds of pressure in nature and in the body as they squeeze through capillaries and adhere to the surfaces of medical devices, for example.

“If you want to understand biofilms and their life cycle, you need to consider their genetics, but also their mechanical properties. You need to think of biofilms as materials that respond to forces, because how they live in the environment depends on that response,” says Mike Solomon, associate professor of chemical engineering and macromolecular science and engineering, who is senior author of the paper.

Mechanical forces are at play when our bodies defend against these bacterial colonies as well, Younger says.

“You can study gene expression patterns as much as you want, but until you know when the materials will bend or break, you don’t really know what the immune system has to do from a physical perspective to fight this opponent.”

Researchers haven’t studied these properties yet because there hasn’t been a good way to examine biofilms at the appropriate scale. The U-M microfluidic device provides the right scale.

If doctors and engineers can gain a greater understanding of how biofilms behave, they could perhaps design medical equipment that is more difficult for the bacteria to adhere to, Younger says.

Lasers can lengthen quantum bit memory by 1,000 times

Physicists have found a way to drastically prolong the shelf life of quantum bits, the 0s and 1s of quantum computers.

These precarious bits, formed in this case by arrays of semiconductor quantum dots containing a single extra electron, easily are perturbed by magnetic field fluctuations from the nuclei of the atoms creating the quantum dot. This perturbation causes the bits essentially to forget the piece of information they were tasked with storing.

A quantum dot is a semiconductor nanostructure that is one candidate for creating quantum bits.

The scientists, including U-M’s Duncan Steel, used lasers to elicit a previously undiscovered natural feedback reaction that stabilizes the quantum dot’s magnetic field, lengthening the stable existence of the quantum bit by several orders of magnitude, or more than 1,000 times.

The findings are published in the June 25 edition of Nature.

“In our approach, the quantum bit for information storage is an electron spin confined to a single dot in a semiconductor like indium arsenide. Rather than representing a 0 or a 1 as a transistor does in a classical computer, a quantum bit can be a linear combination of 0 and 1. It’s sort of like hitting two piano keys at the same time,” says Steel, a professor in the Department of Physics and the Robert J. Hiller Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

“One of the serious problems in quantum computing is that anything that disturbs the phase of one of these spins relative to the other causes a loss of coherence and destroys the information that was stored. It is as though one of the two notes on the piano is silenced, leaving only the other note.”

Spin is an intrinsic property of the electron that isn’t rotation, but is more like magnetic poles. Electrons are said to have spin up or down, which represent the 0s and 1s.

— Nicole Casal Moore, News Service

U.S. seniors “smarter” than their English peers

U.S. senior citizens performed significantly better than their counterparts in England on standard tests of memory and cognitive function, according to a new study.

Kenneth Langa, lead author of the study, and colleagues compared data on 8,299 Americans age 65 and older with 5,276 British seniors.

The U.S. advantage in “brain health” was greatest for the oldest old — those age 85 and older. On a population level, the overall difference in cognitive performance between the two countries was quite large — approaching the magnitude associated with about 10 years of aging.

In other words, the cognitive performance of 75-year-olds in the U.S. was as good, on average, as that of 65-year-olds in England.

Higher levels of education and net worth in the United States accounted for some of the better cognitive performance of U.S. adults, says Langa, a professor of medicine at the Medical School, a research investigator at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, and a faculty associate at the Institute for Social Research (ISR).

U.S. adults reported significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms than English adults, which Langa says may have accounted for some of the U.S. advantage in brain health, since depression is linked with worse cognitive function.

Langa and colleagues also found significant differences in alcohol consumption between the U.S. and English seniors. More than 50 percent of U.S. seniors reported no alcohol use, compared to only 15.5 percent of English seniors.

ISR economist David Weir, director of the Health and Retirement Study and a co-author of the analysis, noted that other ongoing research by ISR economist Robert Willis suggests there may be a connection between early retirement and early onset of cognitive decline. In England retirement occurs earlier than in the United States.

Finally, Langa noted, while U.S. adults reported a higher prevalence of hypertension, they also were more likely to be taking medications to treat the condition.

Data on the U.S. population came from the Health and Retirement Study, conducted by the ISR and funded by the National Institute on Aging. Data on the U.K. study was from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing.

The report is published in the June 25 peer-reviewed journal BMC Geriatrics.

— Diane Swanbrow, News Service

Chemicals in consumer products may play role in pre-term births

A new study of expectant mothers suggests that a group of common environmental contaminants called phthalates, which are present in many industrial and consumer products including everyday personal care items, may contribute to the country’s alarming rise in premature births.

Researchers at the School of Public Health found that women who deliver prematurely have, on average, up to three times the phthalate level in their urine compared to women who carry to term.

Professors John Meeker, Rita Loch-Caruso and Howard Hu of the SPH Department of Environmental Health Sciences, along with collaborators from the National Institute of Public Health in Mexico and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, analyzed data from a larger study directed by Hu. It follows a cohort of Mexican women recruited during pre-natal visits at one of four clinics of the Mexican Institute of Social Security in Mexico City.

In the United States, premature births have increased by more than 30 percent since 1981 and by 18 percent since 1990. In 2004 premature births accounted for 12.8 percent of live births nationwide.

Premature births, he says, account for one-third of infant deaths in the United States, making it the leading cause of neonatal mortality. Being born too early also can lead to chronic health problems such as blindness, deafness, cerebral palsy, low IQ and more.

Phthalates commonly are used compounds in plastics, personal care products, home furnishings (vinyl flooring, carpeting, paints, etc.) and many other consumer and industrial products. The toxicity varies by specific phthalates or their breakdown products, but past studies show that several phthalates cause reproductive and developmental toxicity in animals.

A couple of human studies have reported associations between phthalates and gestational age, but this is the first known study to look at the relationship between phthalates and premature births, Meeker says.

— Laura Bailey, News Service

Second Life data offers window into how trends spread

Do friends wear the same style of shoe or see the same movies because they have similar tastes, which is why they became friends in the first place? Or once a friendship is established, do individuals influence each other to adopt like behaviors?

Social scientists don’t know for sure. They’re still trying to understand the role social influence plays in the spreading of trends, because the real world doesn’t keep track of how people acquire new items or preferences.

But the virtual world Second Life does. Researchers from the university have taken advantage of this unique information to study how “gestures” make their way through this online community. Gestures are code snippets that Second Life avatars must acquire in order to make motions such as dancing, waving or chanting.

Roughly half of the gestures the researchers studied made their way through the virtual world friend by friend.

“We could have found that most everyone goes to the store to buy gestures, but it turns out about 50 percent of gesture transfers are between people who have declared themselves friends. The social networks played a major role in the distribution of these assets,” says Lada Adamic, an assistant professor in the School of Information and the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

Adamic is an author of a paper that graduate student Eytan Bakshy presented July 7 at the Association for Computer Machinery’s Conference on Electronic Conference in Stanford, Calif. Bakshy is a doctoral student in the School of Information. Physics graduate student Brian Karrer is a co-author.

This study is one of the first to model social influence in a virtual world because of the rarity of having access to information about how information, assets or ideas propagate. In Second Life, the previous owner of a gesture is listed.

The researchers also found that the gestures that spread from friend to friend were not distributed as broadly as ones that were distributed outside of the social network, such as those acquired in stores or as giveaways.

And they discovered that the early adopters of gestures who are among the first 5-10 percent to acquire new assets are not the same as the influencers, who tend to distribute them most broadly. This aligns with what social scientists have found.

—Nicole Casal Moore, News Service

Researchers using math to reduce jet lag

Reducing jet lag is the aim of a new mathematical methodology and software program developed by researchers at U-M and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

A major cause of jet lag is the desynchronization of the body’s internal clock and the local environment when a person travels across several time zones. Symptoms include trouble sleeping at night and trouble staying awake during the day.

The new methodology and software program helps users resynchronize their internal clocks with local time using light cues, by giving users exact times of the day when they should apply countermeasures such as bright light to intervene in the normal course of jet lag.

The findings were published in the June 19 issue of PLoS Computational Biology.

“This work shows how interventions can cut by half the number of days needed to adjust to a new time zone,” says Daniel Forger, an assistant professor of mathematics and a research assistant professor in the Department of Computational Medicine and Biology at the Medical School. Forger is an author of the paper.

Timed light exposure is a well-known method for synching an individual’s internal clock with the environment, and when used properly, this intervention can reset that clock to align with local time. This results in more efficient sleep, a decrease in fatigue, and an increase in cognitive performance. Poorly timed light exposure can prolong the re-synchronization process.

Using the computation, researchers simulated shifting sleep and wake schedules and the subsequent light interventions for realigning internal clocks with local times.

Although this method is not yet available to the public, it has direct implications for jet lag, shift-work and scheduling for extreme environments, such as in space, undersea or the polar regions, he says.

—Nicole Casal Moore, News Service

Antibiotics take toll on beneficial microbes in gut

It’s common knowledge that a protective navy of bacteria normally floats in our intestinal tracts. Antibiotics at least temporarily disturb the normal balance. But it’s unclear which antibiotics are the most disruptive, and whether the full array of “good bacteria” return promptly or remain altered for some time.

In studies in mice, U-M scientists have shown for the first time that two different types of antibiotics can cause moderate to wide-ranging changes in the ranks of these helpful guardians in the gut. In the case of one of the antibiotics, the armada of “good bacteria” did not recover its former diversity even many weeks after a course of antibiotics was over.

The findings eventually could lead to better choices of antibiotics to minimize side effects of diarrhea, especially in vulnerable patients. They could also aid in understanding and treating inflammatory bowel disease.

Thousands of different kinds of microbes live in the gut, including many different bacteria. They aid digestion and nutrition, appear to help maintain a healthy immune system, and keep order when harmful microbes invade.

The study results suggest that unless medical research discovers how to protect or revitalize the gut’s microbial community, “we may be doing long-term damage to our close friends,” says Dr. Vincent Young, senior author of the study and assistant professor in the departments of Internal Medicine and Microbiology and Immunology.

Young’s team found that some mice given cefoperazone soon recovered normal microbes after an untreated mouse was placed in the same cage. Mice have a habit of eating the feces of their cage mates and, therefore, picked up normal gut microbes quickly.

Not a lesson applicable to humans?

In patients with refractory antibiotic-associated diarrhea due to C. difficile, there have been limited trials of treatments using “fecal transplants” to replace lost gut microbiota. Although this is a pretty unpalatable treatment at first glance, the clinical response was quite remarkable, Young says.

Although cefaperazone is not commonly used in the United States, related drugs are, such as cefoxitin. The findings suggest it is important to use antibiotics only when indicated, especially in people with health problems that might already compromise their gut microbe health, Young says. Multiple rounds of antibiotics may also deserve concern.

Other authors are: first author Dionysios Antonopoulos, Department of Internal Medicine; Susan Huse, Mitchell Sogin and Hilary Morrison, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Mass.; and Thomas Schmidt, Michigan State University.

—Anne Rueter, UMHS Public Relations