Vehicle fuel efficiency made little progress since 1920s

Vehicles on America’s roads today get only about three miles more per gallon than vehicles back in 1923, researchers say.

A study in the journal Energy Policy by Michael Sivak and Omer Tsimhoni of the U-M Transportation Research Institute (UMTRI) shows that overall fuel efficiency for vehicles in the United States was 14 miles per gallon in 1923 and 17.2 mpg in 2006.

The researchers documented and analyzed the annual changes in actual fuel efficiency of vehicles on U.S. roads from 1923 to 2006 by using information about distances driven and fuel consumed to calculate fuel efficiency. They found that overall fleet fuel efficiency actually decreased from 14 mpg in 1923 to a low of 11.9 mpg in 1973, but then rapidly increased to 16.9 mpg by 1991.

“After the 1973 oil embargo, vehicle manufacturers achieved major improvements in the on-road fuel economy of vehicles,” says Sivak, research professor and head of UMTRI’s Human Factors Division. “However, the slope of the improvement has decreased substantially since 1991.”

From 1991 to 2006, fuel efficiency increased by less than 2 percent, compared with a 42 percent increase in mpg between 1973 and 1991.

According to the study, fuel efficiency for cars improved from 13.4 mpg in 1973 to 21.2 mpg in 1991, but reached only 22.4 mpg by 2006. For light trucks, the numbers were 9.7 mpg in 1966, 17 mpg in 1991 and 18 mpg in 2006. Medium and heavy trucks showed modest improvement from 5.6 mpg in 1966 to 5.9 mpg in 2006.

Researchers say the focus should be on the least-efficient vehicles within each class. For example, an improvement from 40 mpg to 41 mpg for a vehicle driven 12,000 miles per year saves 7 gallons of fuel a year. An improvement from 15 mpg to 16 mpg for a vehicle driven the same amount of miles, however, saves 50 gallons of fuel a year.

Researchers involved in primate fossil find

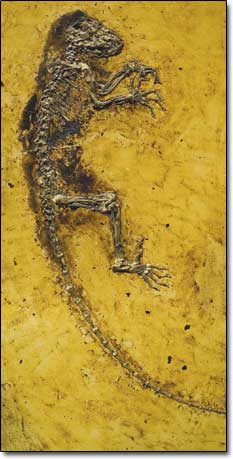

U-M researchers Philip Gingerich and Holly Smith are members of an international scientific team that recently announced discovery of a remarkably complete, well-preserved, 47 million-year-old fossil of an extinct early primate.

Known as Ida, the fossil is thought to represent an early member of the lineage that gave rise to monkeys, apes and humans.

The find is described in a paper published online May 19 in the open-access journal PLoS ONE and also is the subject of a History Channel film, “The Link,” and a book, “The Link: Uncovering Our Earliest Ancestor.”

Ida, a young, agile plant-eater, belonged to a previously unknown genus of primate, which the paper’s authors have named Darwinius masillae. The fossil is 95 percent complete and includes the skeleton, an outline of the animal’s body and the contents of her gut, providing hints to her diet and life history.

“She could have lived as long as 20 years, but she would have been an adult in three to four years,” says Smith, an associate research scientist at the Museum of Anthropology and an authority on the evolution of mammalian dentition. “She was probably a third of the way to being an adult when she died.”

Ida may help resolve a debate over which group of early primates gave rise to humans. One likely candidate is the tarsioid superfamily, whose modern members are tiny, saucer-eyed forest creatures known as tarsiers. This is the group with which adapoids like Darwinius are now shown to be associated. The other is the lemuroid-lorisoid superfamily, which is evidently more distantly related.

The newly described fossil shares key anatomical features with higher primates, bolstering the evidence for a link between ancient adapoids and humans, says Gingerich, professor of geological sciences and director of the U-M Museum of Paleontology.

“Darwinius is really a Rosetta Stone of primate evolution because it links many characteristics we haven’t been able to associate in one animal before,” he says.

— Nancy Ross-Flanigan, News Service

Bad jobs for mom may harm children

The kind of job a woman has may be just as important as whether she works or not when it comes to the well-being of her child. That’s the implication of a new study by researcher Amy Hsin.

“Bad jobs” have been on the rise in the United States for decades. According to one estimate, the share of U.S. labor hours spent in low-paid jobs that require little education has increased by 35 percent since 1980. And for those with less than a college education, the rise in these jobs, most in the service sector, has exceeded 53 percent.

For the study, Hsin, a sociologist at the Institute for Social Research (ISR), and colleague Christina Felfe at the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland), defined bad jobs by the amount of physical hazards and social stress involved.

In general, the researchers found that the worse a mother’s job, the worse their children did on verbal skills. But the mother’s education level had a significant impact on how harmful a bad job was to her kids.

Bad jobs for more educated mothers were different from bad jobs for less educated moms, they found. The most common bad jobs for mothers with high school educations were assemblers, cleaners, foremen and nurse’s aides, for example, while the most common bad jobs for college graduates were registered nurses, therapists and elementary school teachers.

Hsin and Felfe found that moms with bad jobs were spending just as much time with their children as other mothers.

“This suggests that it’s the quality of time mothers are spending with their children that suffers when mothers have bad jobs,” she says. “Because they’ve had such stressful days, they may be less patient, attentive, and responsive than they would otherwise be able to be, and this is what may be having a negative impact on their children’s achievement.”

— Diane Swanbrow, News Service

Study examines tensions between adult children and their parents

The majority of parents and adult children experience some tension and aggravation with one another, a new study says.

But parents generally are more bothered by the tensions — and the older the child, the greater the bother.

“The parent-child relationship is one of the longest lasting social ties human beings establish,” says Kira Birditt, lead author of the study and a researcher at the Institute for Social Research (ISR). “This tie is often highly positive and supportive but it also commonly includes feelings of irritation, tension and ambivalence.”

For the study, which will be featured in the journal Psychology and Aging, Birditt and colleagues at Purdue and Pennsylvania State universities asked about tensions related to a variety of topics, including personality differences, past relationship problems, children’s finances, housekeeping habits, lifestyles and how often they contacted each other.

Parents and adult children in the same families had different perceptions of tension, with parents generally reporting more intense tensions than children did, particularly regarding issues having to do with the children’s lifestyle or behavior (finances, housekeeping). Tensions may be more upsetting to parents than to children because parents have more invested in the relationship, Birditt says.

Both mothers and fathers reported more tension in their relationships with daughters than with sons. Daughters generally have closer relationships with parents that involve more contact, which may provide more opportunities for tensions in the parent-daughter tie.

Both adult sons and adult daughters reported more tension with their mothers than with their fathers, particularly about personality differences and unsolicited advice. “It may be that children feel their mothers make more demands for closeness,” Birditt says, “or that they are generally more intrusive than fathers.”

— Diane Swanbrow, News Service

New system offers intervention to caregivers of dementia patients

Researchers have developed a new system that helps provide intervention to caregivers of patients with dementia.

Family caregivers play a pivotal role in managing the health and care of dementia patients, but the needs of these caregivers are not often assessed, researchers say.

“Although providing care can be rewarding, it often places caregivers at great risk for negative outcomes that also compromise the well-being of the patients with dementia,” says Louis Burgio, a professor in the School of Social Work and a research professor at the Institute of Gerontology. Burgio was one of eight authors of a new study.

Researchers identified 16 risks that dementia caregivers and care recipients confront most often. A risk appraisal provides information that can help clinicians tailor interventions to a caregiver’s individual needs.

The screening form can be administered to the caregiver by any health care professional: physicians, nurses, eldercare agency or social worker. The interventions are most often administered through a social service agency. It has been used in physician’s offices with a nurse or social worker doing the intervention.

“The measure is an efficient and easily administered tool that can provide a road map for intervention,” he says, noting it will also increase the likelihood that a caregiver will receive the specific form of assistance needed to effectively maintain the care-giving role.

Burgio says Hispanic caregivers were at slightly higher risk for depression than other caregivers. Black and Hispanic caregivers, however, reported fewer burdens than white caregivers. White caregivers reported more problems with safety concerns.

Burgio collaborated on the study with researchers at about a half-dozen universities, including the University of Pittsburgh, University of Miami and Stanford University.

— Jared Wadley, News Service

Parents’ trust in doctor key for black children with asthma

Children younger than 12 with persistent asthma need highly motivated parents if they are to get the benefits of regular steroid inhaler treatments and have fewer asthma attacks. That motivation starts with a good relationship between parent and doctor.

But in a recent survey, black parents rated their children’s doctors lower than white parents did in qualities that are linked to better adherence with asthma medications, U-M researchers report.

“For the parents who did not give the medications as prescribed, we found specific characteristics of their experience with the doctor that were associated with less adherence,” says Dr. Kathryn Moseley, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Medical School.

The results suggest improved physicians’ relationships with these parents could help reduce the frequency of asthma attacks and hospitalizations among minority children.

One way to improve parents’ trust and confidence is for clinics to make sure that parents with children who have persistent asthma see the same doctor each time if possible, Moseley says.

The study, which appears in the May issue of the Journal of the National Medical Association, also shows that parents who are not adhering to asthma treatments are in many cases not getting flu shots for their children.

Children who don’t get regular steroid inhaler treatments for their asthma are at higher risk of complications from influenza. So there’s an added reason for physicians to work to increase rapport with minority parents.

Ericka Hudson, a research associate at the Child Health Evaluation and Research Unit, also is an author of the study.

— Anne Rueter, UMHS Public Relations

Chromosome slices offer insight into cell division

By using ultrafast laser pulses to slice off pieces of chromosomes and observe how the chromosomes behave, biomedical engineers at U-M have gained insights into mitosis, the process of cell division.

Their findings could help scientists better understand genetic diseases, aging and cancer.

Cells in plants, fungi, and animals — including those in the human body — divide through mitosis, during which the DNA-containing chromosomes separate between the resulting daughter cells. Forces in a structure called the mitotic spindle guide the replicated chromosomes to opposing sides as one cell eventually becomes two.

“Each cell needs the right number of chromosomes. It’s central to life in general and very important in terms of disease,” says Alan Hunt, an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and an author of a paper describing these findings published in Current Biology.

“One of the really important fundamental questions in biology is how do chromosomes get properly segregated when cells divide. What are the forces that move chromosomes around during this process? Where do they come from and what guides the movements?”

Hunt’s results validate the theory that “polar ejection forces” are at play. Scientists had hypothesized that the direction and magnitude of these forces might provide physical cues guiding chromosome movements. In this capacity, polar ejection forces would play a central role separating chromosomes in dividing cells, but no one had established a direct link until now.

Mitosis, Hunt says, is one of the most important targets of chemotherapy.

“By knowing how chromosomes move, we can better understand how these drugs interfere with those movements and we can design experiments to screen for new drugs,” Hunt says. “It will also allow us to have a better handle on what makes these drugs work. There are a lot of drugs that interfere with mitosis, but only a few are good for cancer therapy.”

— Nicole Casal Moore, News Service

Triglycerides implicated in diabetes nerve loss

A common blood test for triglycerides — a well-known cardiovascular disease risk factor — may also for the first time allow doctors to predict which patients with diabetes are more likely to develop the serious, common complication of neuropathy.

In a study now online in the journal Diabetes, U-M and Wayne State University researchers analyzed data from 427 diabetes patients with neuropathy, a condition in which nerves are damaged or lost with resulting numbness, tingling and pain, often in the hands, arms, legs and feet.

The data revealed that if a patient had elevated triglycerides, he or she was significantly more likely to experience worsening neuropathy over a period of one year. Other factors, such as higher levels of other fats in the blood or of blood glucose, did not turn out to be significant. The study will appear in print in the journal’s July issue.

“In our study, elevated serum triglycerides were the most accurate at predicting nerve fiber loss, compared to all other measures,” says Kelli Sullivan, co-first author of the study and an assistant research professor in neurology at the Medical School.

“These results set the stage for clinicians to be able to address lowering lipid counts with their diabetes patients with neuropathy as vigilantly as they pursue glucose control,” says Dr. Eva Feldman, senior author of the study and the Russell N. DeJong Professor of Neurology at the Medical School.

With a readily available predictor for nerve damage — triglycerides are measured as part of routine blood testing — doctors and patients can take proactive steps when interventions can do some good, Feldman says.

People can reduce blood triglyceride levels with the same measures that reduce cholesterol levels: by avoiding harmful fats in the diet and exercising regularly.

Other authors include Timothy Wiggin, co-first author, director of biomedical informatics at U-M’s Juvenile Diabetes Research Center; Dr. Anders Sima, professor of pathology and neurology at Wayne State University Medical School; and Dr. Antonino Amato from Sigma-Tau Research.

— Anne Rueter, UMHS Public Relations

Snail venoms reflect reduced species competition

A study of venomous snails on remote Pacific islands reveals genetic underpinnings of an ecological phenomenon that has fascinated scientists since Darwin.

The research, by U-M evolutionary biologists Tom Duda and Taehwan Lee, is published online in the open-access journal PLoS ONE.

In the study, Duda and Lee explored ecological release, a phenomenon thought to be responsible for some of the most dramatic diversifications of living things in Earth’s history.

Ecological release occurs when a population is freed from the burden of competition, either because its competitors become extinct or because it colonizes a new area where few or no competitors are found. When this happens, the “released” population typically expands its diet or habitat, taking over resources that would be off-limits if competitors were present. This expansion is believed to drive the evolution of adaptations for taking advantage of the new resources, such as venoms tailored to a broader array of prey.

“Although there are plenty of examples of populations expanding into a variety of niches after experiencing ecological release, little is known about the evolution of genes associated with this phenomenon,” says Duda, an assistant professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

To investigate the process, Duda and Lee took advantage of a natural experiment involving a species of cone snails found in shallow waters of tropical to subtropical environments from the Red Sea and eastern shores of Africa in the western Indian Ocean to Easter Island and Sala y Gomez in the southeastern Pacific.

In most areas where the species is found, the snails have lots of competitors and prey on only three species of marine worms. But on Easter Island, where it has virtually no competition, the snail’s diet is much broader, incorporating many additional species of worms. Cone snails paralyze their prey with venom made up of various “conotoxins.”

“On Easter Island, where the snails are eating far more things than they’re eating elsewhere, we see that different toxins predominate, suggesting that natural selection has operated at these toxin genes,” says Duda, who also is a research associate with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

— Nancy Ross-Flanigan, News Service