By Joanne Nesbit

News and Information Services

He was the 26th president of the United States, won the Nobel Peace Prize for mediating the Russo-Japanese War, and stands 60 feet tall in the Black Hills of South Dakota along with Washington, Jefferson and Lincoln. But Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt’s real claim to fame may be as the father of the annual Army-Navy football game.

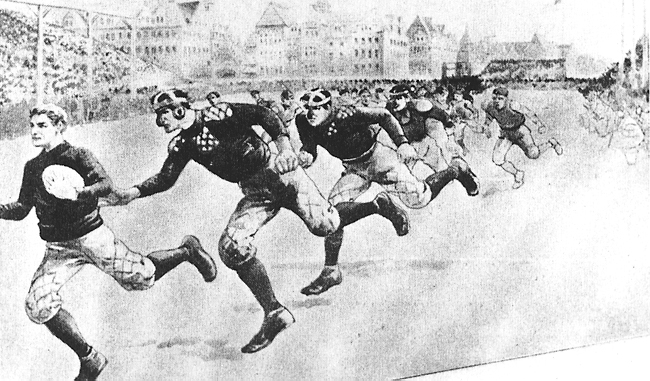

Roosevelt (1858–1919) was not only an energetic and forceful president, but an accomplished author, historian, journalist and ardent sportsman. As assistant secretary of the Navy, he advocated resumption of the Army-Navy football contests that were suspended in 1893 because of disciplinary problems. The first game on Nov. 29, 1890, was a shutout of the host Cadets with Red Emerich scoring 20 of Navy’s 24 points and Moulton Johnson adding the other touchdown. Touchdowns at that time were worth four points, bringing the final score to Navy 24, Army 0.

The Army-Navy game of 1893, won by Navy with a score of 6-4, was so bloody—with several free-for-all fights in the stands—that President Grover Cleveland banned the contest for five years.

A letter from Roosevelt resulted in the resumption of the series in 1899. That series was interrupted in 1917–18 during World War I as a sign of unity and again in 1928–29 after bad feelings flared up regarding what some reported to be a controversy regarding eligibility. There were no regular season games scheduled for 1930–31 but the two academy teams did meet at Yankee Stadium for charity games, organized to raise funds for relief of the unemployed during the early years of the Great Depression. Army won both of those games. The series has not been interrupted since.

“What makes this letter to Secretary of War Russell A. Alger particularly fascinating,” says John Dann, director of the Clements Library where Roosevelt’s original letter resides, “is the timelessness of the potential problems with collegiate athletics that Roosevelt identifies—favoritism shown to athletes, relaxation of academic and behavioral standards for star players, disruption of educational routines and gambling— the same dangers that continue to threaten big-time athletic programs to this day.”

Navy Department

Office Assistant Secretary

Washington August 17, 1897

My dear General Alger:

For what I am about to write you I think I should have the backing of my fellow-Harvard man, your son. I should like very much to revive the football games between Annapolis and West Point. I think the Superintendent of Annapolis, and I dare say Colonel Ernst, the Superintendent of West Point, will feel a little shaky because undoubtedly formerly the academic routine was cast to the winds when it came to these matches, and a good deal of disorganization followed. But it seems to me that if we would let Colonel Ernst and Captain Cooper come to an agreement that the match should be played just as either eleven plays outside teams; that no cadet should be permitted to enter or join the training table if he was unsatisfactory in any study or conduct, and should be removed if during the season he becomes unsatisfactory; if they were marked without regard to their places on the team; if no drills, exercises or recitations were omitted to give opportunities for football practice; and if the authorities of both institutions agreed to take measures to prevent any excesses such as betting and the like, and to prevent any manifestations of an improper character—if as I say all this were done—and it certainly could be done without difficulty—then I don’t see why it would not be a good thing to have a game this year.

If you think favorably of the idea, will you be willing to write Colonel Ernst about it?

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt