Quick view:

A hidden cost of depression: Extra help for depressed seniors>

It’s never too late to lose weight>

Guiding gas exploration: Research offers inexpensive tool>

Top-selling book focuses on Toyota’s methods>

Iron-deficient infants score worse on tests as teens>

Ultra-fast laser allows efficient, accessible nanoscale machining>

Botox for the voice>

Childhood sleep problems can predict adolescent substance use>

Women need not lose sleep over menopause>

Chemical brain scans may help reassure brain tumor patients>

Oakland County turns corner, returns to sustained job growth>

Black men less likely to be treated for aggressive prostate cancer>

Men with family history of prostate cancer know their risk>

Mutual fund investors: Don’t shoot for the stars>

Physics researchers find striking quantum spin behavior>

Insulin pump benefits preschoolers with diabetes>

Second-hand smoke triggers kids’ year-round asthma symptoms>![]()

A hidden cost of depression: Extra help for depressed seniors

A study reveals that depression among senior citizens carries a huge unrecognized cost: many extra hours of unpaid help with everyday activities, delivered by the depressed seniors’ spouses, adult children and friends.

Even moderately depressed seniors, the study finds, require far more hours of care than those without any symptoms of depression, regardless of other health problems they may have. If “informal” caregivers for depressed seniors were paid the wages of a home health aide, the cost to society would be $9 billion a year, the researchers estimate. That puts depression second only to dementia in the national annual cost for informal caregiving, based on previous studies of the same data.

The findings, published in the May issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry, are based on data from U-M’s Health and Retirement Study, a long-term survey of older Americans conducted by the Institute for Social Research (ISR). The study’s authors, from the U-M Health System’s departments of Internal Medicine and Psychiatry and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, analyzed data from 6,651 people older than 70 from around the nation. It is the first analysis of its kind.

The survey showed that 38 percent of seniors who had many depressive symptoms, and 23 percent of those with a few symptoms, reported receiving informal care from family or friends—but only 11 percent of those without depressive symptoms did.

“People with many depressive symptoms also had a significantly higher likelihood than others of needing help with tasks such as dressing, bathing, eating, grocery shopping, taking medicines, paying bills and using the telephone,” says lead author Dr. Ken Langa, assistant professor of general medicine and faculty associate of ISR.

Dr. Marcia Valenstein, a U-M psychiatrist who treats older people with depression at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, was co-author. Dr. Sandeep Vijan, was senior author. Other authors were Dr. Mark Fendrick and Mohammed Kabeto. The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association.

It’s never too late to lose weight

Don’t give up the fight against fat even when the years are piling up faster than the pounds. A study in the April 2004 issue of The Gerontologist shows that obesity has a dramatic impact on an older person’s chances of leading an active and independent life.

“The findings point to some good reasons why it is important for seniors to maintain a healthy weight,” says Kristi Rahrig Jenkins, a sociologist at the Institute for Social Research (ISR) and the author of the article, “Obesity’s Effects on the Onset of Functional Impairment Among Older Adults.”

Jenkins analyzed data on 4,087 men and women age 70 and older from the ISR Health and Retirement Study, funded by the National Institute on Aging. About 46 percent were normal weight, as determined by their body mass index, while 37.2 percent were overweight and 13.5 percent were obese.

Even when Jenkins controlled for health behaviors including smoking, binge drinking and exercising, and for health conditions and symptoms, she found that obese seniors were twice as likely as their normal weight peers to develop problems with strength (including getting up from a chair after sitting for long periods) and lower-body mobility (including walking a block and climbing a flight of stairs).

They also were much more likely than normal-weight seniors to report having trouble dressing and bathing themselves, eating or getting out of bed.

—Diane Swanbrow, News Service

Guiding gas exploration: Research offers inexpensive tool

Freshwater from melting ice sheets set the stage several thousand years ago for production of natural gas along the margins of sedimentary basins. Now researchers at U-M and Amherst College are reading chemical signatures of water in those areas to pinpoint places where gas most likely is to be found. Their most recent work is described in the May/June issue of the Geological Society of America Bulletin.

Natural gas forms when organic materials trapped in sediments decompose, either when the materials are exposed to high temperatures—producing thermogenic gas—or when bacteria break down the organic matter and, through the process of methanogenesis, produce microbial gas. Finding and exploiting microbial gas deposits, which account for as much as 20 percent of the world’s natural gas resources, is “becoming more and more important,” says doctoral student Jennifer McIntosh, lead author of the paper. And identifying areas where methanogenesis has occurred can help pinpoint microbial gas deposits.

McIntosh and coauthors Lynn Walter, U-M professor of geological sciences, and Anna Martini, Amherst College assistant professor of geology, studied Antrim Shale deposits in the Michigan Basin, a deep depression filled with sediments that date back to the Paleozoic Era. In previous work, the researchers showed that freshwater seeping into the basin’s shallow edges from melting ice sheets created an environment that was conducive to methanogenesis within organic-rich black shales.

In the current work, the research team compared the chemistry of water from wells drilled in the deeper center of the basin with that of water from wells at the edges. Their analysis provided further evidence that melting ice sheets made it possible for methane-producing bacteria to inhabit the shallow deposits and also showed that methanogenesis significantly has changed water chemistry in those areas. “So you can use the elemental chemistry of these shale wells to be able to tell if there was methanogenesis, and that guides gas companies in terms of where to explore for microbial gas,” McIntosh says. “It’s a relatively inexpensive analytical tool, compared to other methods that have been used, such as stable isotope chemistry.” The method has potential not just in Michigan, but also the Illinois basin and other parts of the world that have similar black shale deposits, McIntosh says.

The research was funded in part by the Petroleum Research Fund, administered by the American Chemical Society, and by the Gas Research Institute.

—Nancy Ross-Flanigan, News Service

Top-selling book focuses on Toyota’s methods

Most companies fall short of implementing true lean principals because they focus on short-term gains through the so-called surface tools of lean, such as creating cells, and do not create a true lean culture, Professor Jeffrey Liker says.

Liker, a nationally recognized expert in lean manufacturing, outlines in his book the 14 principles of lean manufacturing that comprise the Toyota methods of lean production and talks about why most companies haven’t caught on.

“Toyota will invest $5 today with the belief that they will get $100 in two years,” says Liker, author of “The Toyota Way,” which has become a surprise top-seller in the business management book category and is being translated into six languages just three months after its January release. “American companies won’t do that unless I can show them today, in extraordinary detail, how they will get $10.”

Critical to the lean system are developing people and partners, but many companies fail here. For example, the Big Three automakers struggle with labor issues and continuously squeeze suppliers to make short-term revenue gains, he says.

The management principles in “The Toyota Way” may be applied to any business, large or small. That is why editors at publisher McGraw-Hill Trade believe the book is popular.

Liker, a professor of industrial and operations engineering, is the director of the Japan Technology Management Program and co-director of the lean manufacturing program at U-M.

—Laura Bailey, News Service

Iron-deficient infants score worse on tests as teens

Teens who suffered iron deficiency as infants are likely to score lower on cognitive and motor tests, even if that iron deficiency was identified and treated in infancy, a U-M study shows.

Betsy Lozoff, who has studied iron deficiency for nearly three decades, followed Costa Rican children who were diagnosed with severe, chronic iron deficiency when they were 12-23 months old and were treated with iron supplements.

She and collaborators examined 191 children in working- to middle-class families at 5 years, 11-14 years and again at 15-17, and they found the iron-deficient babies grew up to lag their peers in both motor and mental measures.

Lozoff presented “Longitudinal Analysis of Cognitive and Motor Effects of Iron Deficiency in Infancy” at the Pediatric Academic Societies’ annual meeting May 3 in San Francisco.

Children who had good iron status as babies showed better motor skills than those who had been iron deficient, says Lozoff, director of the Center for Human Growth and Development and professor in the Department of Pediatrics and Communicable Diseases.

That gap remained throughout childhood and adolescence. “There is no evidence of catch up.”

Even worse were the cognitive measures: Children who previously had suffered iron deficiency not only lagged behind their peers, but the difference increased over time. They scored about six points lower on cognitive tests at age 1-2 years and 11 points lower at age 15-18 years.

Lozoff’s collaborators on the study were Julia Smith, Tal Liberzon, Rosa Angulo-Barroso, Agustin Calatroni and Elias Jimenez.

—Colleen Newvine, News Service

Ultra-fast laser allows efficient, accessible nanoscale machining

Think of a microscopic milling machine, capable of cutting just about any material with better-than-laser precision, in 3-D—and at the nanometer scale.

|

|---|

|

Optics at critical intensity: Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of nanometer scale holes are shown with an illustrated overlay of the laser beams that produced them. Because the threshold for material damage becomes extraordinarily sharp and predictable for sub-picosecond pulses, diffraction ceases to be a limiting factor, and the effective “machining” diameter varies with pulse energy even though the focused spot size is invariant. (Courtesy Ajit Joglekar) |

In a paper published last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U-M researchers explain how and why using a femtosecond pulsed laser enables extraordinarily precise nanomachining. The capabilities of the ultra-fast or ultra-short pulsed laser have significant implications for basic scientific research, and for practical applications in the nanotechnology industry.

Initially, the researchers working at the Center for Ultrafast Optical Science wanted to use the ultra-fast laser as a powerful tool to study structures within living cells, says Alan Hunt, assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering.

“It turned out we could push much farther than expected, and the applications became broad, from microelectronics applications to MEMS [microelectromechanical systems] to microfluidics,” Hunt says. One of the most perplexing problems in nanotechnology is finding an efficient and precise way to build and machine the tiny devices. For example, a human hair is about 100,000 nanometers across.

The unique physics of an ultra-short pulsed laser used at a very high intensity make it possible to selectively ablate or cut away features as small as 20 nanometers, Hunt says. This is possible because of the way extremely short pulses of light interact with matter, specifically by using femtosecond pulses, a blast of light just a quadrillionth of a second long.

The research team included Hunt; Gerard Mourou, professor of electrical engineering and computer science; Ajit Joglekar, who recently completed his doctorate in biomedical engineering; Hsiao-hua Liu, a post doc at the Center for Ultrafast Optical Science; and Edgar Meyhofer, associate professor of biomedical engineering and mechanical engineering.

—Laura Bailey, News Service

Botox for the voice

An injection best known for smoothing wrinkles also helps restore the voices—and the confidence—of people with a voice disorder caused by spasms in their vocal cord muscles, a U-M Health System (UMHS) study finds.

Botulinum toxin type A, known as Botox, has been used off-label for years to help people with spasmodic dysphonia, a rare and often-misdiagnosed voice disorder that makes the voice sound strained, broken or breathy. The shots relax the muscles in the vocal cords, just as they do to the muscles in the furrowed foreheads of those who use Botox for cosmetic reasons.

But until now, no long-term data have been available on how the repeated injections affect both patients’ voices, and the emotional, social and physical functioning issues that collectively make up what experts call voice-related quality of life, or V-RQOL. Those answers have been published by a team from the UMHS Vocal Health Center and Department of Otolaryngology. The effect is striking, researchers say.

In the April issue of the Archives of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, the team reported results from a prospective study of 36 patients with the adductory form of spasmodic dysphonia who were treated with Botox up to six times. Nearly all showed dramatic and reproducible improvement on a standardized questionnaire that measured their V-RQOL. The results also counter previous suspicions that the effect of Botox diminishes after repeated injections, and they show that when it comes to the personal, subjective issue of how a voice problem affects a person’s well-being, the injections produce a powerful and sustained improvement.

The senior author was Dr. Norman Hogikyan, director of the UMHS Vocal Health Center and associate professor at the Medical School and in the Division of Vocal Arts at the School of Music. Other authors from U-M include Constance Spak, Paul Kileny and former U-M resident Dr. Adam Rubin. The development of the V-RQOL instrument used U-M funding in the 1990s; the current research was funded internally. None of the authors has any financial interest in Botox or its manufacturers.

—Kara Gavin, UMHS Public Relations

Childhood sleep problems can predict adolescent substance use

A long-term study has found a significant connection between sleep problems in children’s toddler years and the chance that they’ll use alcohol, cigarettes and drugs early in their teen years. Young teens whose preschool sleep habits were poor were more than twice as likely to use drugs, tobacco or alcohol.

|

|---|

| Young teens whose preschool sleep habits were poor were more than twice as likely to use drugs, tobacco or alcohol. |

The surprising finding, made by a U-M Health System team as part of a family health study that followed 257 boys and their parents for 10 years, held true even after other issues such as depression, aggression, attention problems and parental alcoholism were taken into account. Long-term data on girls are not yet available.

The researchers suggest that early sleep problems may be useful as a “marker” for predicting later risk of early adolescent substance use—and that there may be a common biological factor underlying both traits. The relationship between sleep problems and the use and abuse of alcohol in adults is well known, but this is the first study to look at the issue in children.

Researchers also emphasize that parents should take the finding only as one more reason to focus on healthy sleep habits for their children, not as a reason to worry.

The findings were published in the April issue of Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research by a team from the U-M Addiction Research Center (UMARC), in the Department of Psychiatry, and a colleague from Michigan State University.

The senior author was UMARC director Robert Zucker. Lead author was research assistant professor Maria Wong. Dr. Kirk Brower, psychiatry professor and executive director of the Chelsea Arbor Treatment Center, was co-author.

To read more, visit http://www.med.umich.edu/opm/newspage/2004/sleeptoddlers.htm.

—Kara Gavin, UMHS Public Relations

Women need not lose sleep over menopause

Can’t get a good night’s sleep? Don’t be quick to blame it on menopause.

Middle-aged women often complain that they sleep poorly, and both women and their health care providers point to menopause as the cause. But researchers Jane Lukacs and Nancy Reame say it may be time to put that assumption to rest.

In an article in the April issue of the Journal of Women’s Health, Lukacs, assistant research scientist at the School of Nursing, under the direction of nursing professor Reame, tested the connection between the hormone estrogen and women’s sleep quality. Her conclusion: “Estrogen has been blamed for a lot, but that doesn’t seem to be what’s at work here.”

Lukacs and her collaborators found total sleep time, time spent awake during the night and efficiency of sleep time all were worse for older women than younger women, regardless of whether the older women still were having menstrual cycles and regardless of whether they used estrogen therapy. Further, although many women have taken hormone replacement drugs to try to help their sleep, Lukacs and Reame found that for women who were not having hot flashes, there was little difference in sleep between post-menopausal women who were or were not taking estrogen supplements.

Other co-authors on the article were Julie Chilimigras and Sharon Dormire of the School of Nursing and Jason Cannon, a Rackham student. The work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, while Lukacs was a Pfizer post-doctoral fellow at the School of Nursing.

—Colleen Newvine, News Service

Chemical brain scans may help reassure brain tumor patients

Brain tumor survivors live with the constant worry that their cancer might come back. And even if they have a brain scan every few months to check, doctors often can’t tell the difference between new cancer growth and tissue changes related to their treatment with radiation or chemotherapy.

A new U-M study shows that a relatively new kind of brain scan may give patients the reassurance or early warning they can’t get from the usual scans. Radiologists presented the evidence last week at the annual meeting of the American Roentgen Ray Society, a major radiology organization.

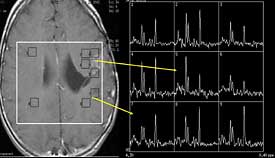

|

|---|

| Signs that cancer has come back: The MRI image on the left is from a young boy who had surgery, chemotherapy and radiation for a brain tumor and had this follow-up MRI that showed a possible recurrence. The small boxes on the MRI correspond to the spectroscopy “chemical thumbprints” on the right; the peaks on the graph indicate levels of certain chemicals in those areas. The top arrow, from the suspicious area, points to the graph showing a high level of a chemical known to be linked to cancer. The bottom arrow points to a graph from a non-suspicious area; the level for that same chemical is much lower. The boy had surgery to confirm the diagnosis, and indeed the cancer had returned. (Image courtesy UMHS) |

The approach is called 2D CSI MRS, short for two-dimensional chemical shift imaging magnetic resonance spectroscopy. It allows doctors to detect the levels of certain chemicals in brain tissue non-invasively. Using the relative quantities of these chemicals, doctors can tell what’s really going on near a tumor’s original location.

Team members showed that they have developed a way to use the technique so that, in the vast majority of cases, they can tell the difference between recurring tumor, normal tissue, and tissue that’s inflamed or dying because of successful treatment.

The researchers are looking forward to the arrival of advanced three-Tesla MRI scanners that will increase their ability to look for more chemicals on the 2D CSI scans, and allow them to do three-dimensional scans that will increase accuracy even more. At the same time, they hope their results will help physicians and insurance companies see the clinical value of 2D CSI MRS, which is not universally covered by health plans in an amount sufficient to cover the time needed to read the scans.

Dr. Patrick Weybright, a radiology resident, presented the results. The senior author was Dr. Pia Maly Sundgren, associate professor of radiology.

—Kara Gavin, UMHS Public Relations

Oakland County turns corner, returns to sustained job growth

Oakland County will gain nearly 46,000 jobs from the end of last year through 2006—recouping most of the county’s job losses of the past three years, U-M economists say.

The county will gain 15,600 jobs from the end of 2003 to the end of this year, add another 16,400 jobs by the end of next year and an additional 13,800 workers by the end of 2006, they say.

“Has the Oakland economy turned the corner, and is it returning to a regime of sustained growth? Our answer is yes and yes,” says George Fulton, economist at the Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations (ILIR), part of the Business School and School of Social Work. “The county economy began gaining jobs at the end of last year and will continue to add jobs from there.”

In their annual forecast of the Oakland County economy, Fulton and ILIR colleague Don Grimes say that more than 90 percent of the new private-sector jobs in the next three years will be in the service-providing sector—professional and business services (15,200 new jobs); financial activities (5,900 new jobs); private education and health services (4,600 new jobs); trade, transportation and utilities (4,400 new jobs); and leisure and hospitality (4,100 new jobs).

—Bernie DeGroat, News Service

Black men less likely to be treated for aggressive prostate cancer

Black men with the most aggressive form of prostate cancer are less likely than white men to receive surgery or radiation therapy, according to a study by U-M Health System (UMHS) researchers.

This racial difference in treatment may be one reason Black men are more likely to die from the disease, the study authors suggest. The paper appeared in the April 2004 issue of the Journal of Urology.

Researchers compared treatments for Caucasian, Hispanic and African-American men from 1992-99. Data from 142,340 men were obtained from the national Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registry, a population-based cancer registration system maintained by the National Cancer Institute.

The men were divided into categories based on whether they received watchful waiting or definitive treatment—which includes surgery, external beam radiation therapy or brachytherapy (in which high-dose radioactive seeds are implanted in the prostate). Black men with moderate grade cancers were 36 percent less likely than white men to receive treatment, and Hispanic men were 16 percent less likely than white men to receive treatment. The racial disparity was even more pronounced among men whose tumors were aggressive.

The lead author was Dr. Willie Underwood, assistant professor of urology surgery in the Medical School. Dr. John Wei, assistant professor of urology in the Medical School, was senior author. Other authors were Sonya Demonner, a biostatistician; Dr. Peter Ubel, associate professor of internal medicine; Angela Fagerlin, research investigator in internal medicine; and Dr. Martin Sanda, associate professor of urology and internal medicine.

Funding for the study came from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program.

—Nicole Fawcett, UMHS Public Relations

Men with family history of prostate cancer know their risk

When a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer, his brothers are twice as likely to develop the disease as well, often at an earlier age.

Research finds these brothers are aware of their increased risk and many have taken vitamins or supplements to improve their health. The research is reported in two papers from the U-M Health System (UMHS).

Men participating in the research study said they felt they had a 50 percent chance of developing prostate cancer within their lifetimes, and more than half of the 111 men surveyed said they were at least somewhat concerned about developing the disease. Lifetime risk for men with one first-degree relative with prostate cancer is about 56 percent, suggesting that the men surveyed were accurately assessing their risk. Results of the study were published in the April 1 issue of Cancer.

In a related study, researchers asked the same group of men about their use of complementary and alternative medicine. More than half said they currently were taking at least one vitamin or supplement and 30 percent were using a type of complementary medicine linked to prostate health or prostate cancer prevention. Results of that study were published in the February issue of Urology.

“These findings suggest our educational programs are working,” says study author Dr. David Wood, professor of urology at the Medical School and a member of the Michigan Urology Center at UMHS. “The information is out there, and these people understand they’re at risk.”

The men in the study were selected from the Prostate Cancer Genetics Project, a large family-based study of inherited forms of prostate cancer led by Dr. Kathleen Cooney, associate professor of internal medicine and urology at the Medical School and senior author on these studies. The lead author was Jennifer Beebe-Dimmer, research fellow in the Department of Urology at the Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Other authors on both studies were Dr. Stephen Gruber from the departments of Internal Medicine, Human Genetics and Epidemiology and Kimberly Zuhlke from the Department of Internal Medicine. Additional authors on the Cancer paper were Doug Chilson and Gina Claeys, both from Internal Medicine. Additional authors on the Urology paper were Julie Douglas, Department of Human Genetics, and Joseph Bonner, Caroline Mohai and Cassandra Shepherd, all from Internal Medicine.

Funding for the studies came from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and an NIH Prostate Cancer S.P.O.R.E. (Specialized Program of Research Excellence) grant.

—Nicole Fawcett, UMHS Public Relations

Mutual fund investors: Don’t shoot for the stars

Top-performing or “star” mutual funds may be a boon to their fund families, but investors should beware of mutual fund companies that employ “star-creating” strategies, Business School researchers say.

While a star fund can cause strong, positive “spillover” effects resulting in greater cash inflow to other funds in its family, it usually is mutual fund families with poor investment abilities that adopt a star-creating approach, according to a study forthcoming in the Review of Financial Studies.

“Investment strategies that are effective in generating stars—by having a large number of funds pursue very different investment strategies so that by chance one might emerge as a star fund are also the ones associated with lower average performance,” says Lu Zheng, assistant professor of finance. “A star-creating strategy, presumably targeted to less-informed investors, does them no favor.”

In their study, “Family Values and the Star Phenomenon,” Zheng and Business School colleagues Vikram Nanda and Z. Jay Wang examined the performance of all diversified U.S. equity funds during a seven-year period in the 1990s. They define a star fund as ranking among the top 5 percent in performance in the previous 12 months (the empirical results remain similar when they alternatively define a star fund as a Morningstar 5-star-rated fund).

The researchers found that new money growth for families with a star fund is, on average, 4.4 percent higher on an annual basis than for families with no stars. In other words, a star family attracts an average of $181 million more than a non-star family on a yearly basis.

—Bernie DeGroat, News Service

Physics researchers find striking quantum spin behavior

A U-M physics professor and his team recently found striking behavior when, for the first time, they manipulated tiny spinning particles called “bosons,” then used quantum mechanics to derive a new formula that exactly described the bosons’ unexpected spin behavior.

Scientists sometimes want to orient particles’ spins in a single direction in order to study the effect of spin on the scattering process, which in turn reveals a sort of medical scan of the particles’ interior. The team used beams of heavy hydrogen nuclei called deuterons. Because their spin value is exactly twice that of the more familiar elementary particles called protons and electrons, the deuterons are called bosons.

The behavior of spinning bosons is different from that of spinning electrons and protons, which can be described fully by their vector polarization. Describing spinning bosons also requires a tensor polarization, which has one more dimension than a vector polarization.

A speculative, but perhaps possible, application of this research comes from the spinning bosons’ extra dimension. This might make the still-speculative but promising quantum computers more effective, because much more information could be stored in the extra dimension—a lake can hold much more water than a narrow stream, says physics Professor Alan Krisch.

The main result of this basic research is the demonstration of yet another phenomenon that can only be explained by the elegant but hard-to-believe theory called quantum mechanics, and by the still-mysterious quantity called spin, which apparently can only have values of exactly one, two, three or four times the electron’s and proton’s exactly equal single-spin-values, Krisch says.

The new COSY data were presented at the May meeting of the American Physical Society in Denver in a preliminary report prepared by graduate student Vasily Morozov and Krisch, who led the team of researchers from U-M, Illinois Tech, and Bonn University and the Research Center Julich in Germany.

—Laura Bailey, News Service

Insulin pump benefits preschoolers with diabetes

Adults and older kids with diabetes who use a pump to deliver insulin have better control of their diabetes and more flexibility during mealtimes than when they relied on daily insulin shots.

Now, the results of a pilot study from the U-M Health System suggest the pump is just as effective as insulin injections at controlling Type 1 diabetes in preschool-aged children—and with less stress and worry for parents.

The study, presented May 1 at the Pediatric Academic Societies’ annual meeting in San Francisco, looked at 16 children ages 3-5 with diabetes. The children were assigned randomly to get either insulin pump therapy or insulin injection treatment.

The children’s blood sugars were measured, and each child was given a special sensor for 72 hours that continuously tracked blood sugars to show how stable they were over time. Parents were asked about quality of life issues related to their child’s diabetes care. Families were seen in clinic once a month for medical care and diabetes education. After six months, the researchers repeated the blood sugar testing and quality of life assessment.

Blood glucose levels remained stable for both groups and there were no differences between the groups in episodes of high or low blood sugars, suggesting effective diabetes management by both the pump and injections.

“Based on this data, the pump is an effective and safe method of managing diabetes in young kids,” says Lisa Opipari-Arrigan, clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Medical School and adjunct clinical assistant professor in the Department of Psychology.

The study was funded by the C.S. Mott Foundation. In addition to Opipari-Arrigan, study authors were research fellow Emily Fredericks, nurse practitioner Nugget Burkhart, clinical care coordinator Linda Dale, nutritionist Mary Hodge, research fellow Jessica Kichler, research associate Pamela Olton and professor of pediatric endocrinology Dr. Carol Foster, all from the Department of Pediatrics.

—Nicole Fawcett, UMHS Public Relations

Second-hand smoke triggers kids’ year-round asthma symptoms

Children with asthma whose parents smoke at home are twice as likely to have asthma symptoms all year long than children of non-smokers, a new study shows.

Overall, in a nationwide sample of children with asthma, about 13 percent of parents of asthmatic children still smoke—even though second-hand smoke is known to trigger asthma attacks and symptoms in kids.

Those findings, made by U-M researchers and presented last week at the Pediatric Academic Societies’ annual meeting, reinforce the importance of educating parents about how their smoking can affect their children with asthma.

Interviews with parents of asthmatic children were done as part of the Physician Asthma Care Education (PACE) project, which is designed to improve asthma education for physicians, and consequently the health of their young patients who have asthma. The chronic condition affects one in every seven children.

The analysis was conducted by Kathryn Slish, researcher in the Department of Pediatrics, with assistant professor of pediatrics Dr. Michael Cabana. The PACE project is led by School of Public Health Dean Noreen Clark and funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

“We set out to look at children who have seasonal asthma symptoms but found that a substantial percentage have symptoms year-round,” Slish says. “We looked more closely and found a strong relationship between parents’ smoking status and the likelihood that their child would have problems all year long. It’s astounding that so many parents smoke around their asthmatic kids, and don’t stop even though their children are having trouble breathing all year.”

—Kara Gavin, UMHS Public Relations