By Rebecca A. Doyle

“I was a teenager when I first realized there were horses in the Olympics,” says Mary Green, “and it has been my dream since then to represent my country in the Olympics.”

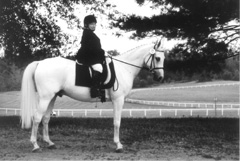

This year the 4-foot-8-inch office assistant in the Office of Space Analysis will get to live her dream. She is a member of the six-person equestrian team that will compete in the 2000 Paralympics in Australia this fall.

Green was born with spina bifida and underwent surgery at University Hospital when she was 3 years old. She was born with a portion of her spinal cord outside the protective column of bone.

Neither the doctors nor her parents knew whether she would ever walk again, but they didn’t tell her that. After the 1951 surgery, Green nonchalantly walked the length of the physical therapy ramp. “They never told me I might not be able to,” she says. She was one of the few people in those days who could walk after surgery that affected the complex nerve system in the spine, she notes.

Doctors recommended horseback riding as therapy, and Green’s parents readily agreed and bought her a pony. She began riding when she was 4. The rocking motion helps keep the back supple, necessary before beginning to strengthen muscles.

“Then, as you learn to control the horse, that helps strengthen the muscles,” Green says.

By age 12, she was riding regularly and began to show on the 4H circuit in Jackson County. She began teaching other children how to care for horses and ponies. Later, her teaching experience became a career after she attended Morven Park International Equestrian Institute in Leesburg, Va. She worked at stables in Virginia and New York before returning home in 1990. Teaching allowed her to help “open up a new world to some of the people who thought they couldn’t do anything like this,” Green says. She proudly notes that about 80 percent of her students are still involved with horses in some way.

In preparation for her Paralympic bid, Green will spend much of her time this summer in training and competitive equestrian events. This month, she will travel to Gladstone, N.J., the headquarters for the National Equestrian Team, for the Festival of Champions. She will train for a few days, then show June 24–25 in freestyle competition—paces and turns set to music.

In competitions, Green explains, each rider uses a “borrowed” horse—one that is supplied for the event by its sponsors. Each rider is allowed only three hours to practice with the horse and teach it the routines before competition. She says she hopes to get a horse that responds to music and will fit her style and needs. Specially trained horses are necessary for Paralympic competition and for other disabled riding competitions because the participants have varied abilities. “The horses must be specifically trained for the movement we do. They need to be very obedient, gait-trained, tolerant of the riders who have spastic movements of arms and legs,” Green says.

Green notes that she never thought of herself as a disabled rider, only as a horsewoman. But in 1993 she heard about a disabled equestrian team that was traveling to the world competition, and wrote to the U. S. Cerebral Palsy Athletic Association for information. A year later, she traveled to England to compete in the World Championships. Her placement helped qualify her for a possible spot on the Paralympic team, but there were still hurdles.

Green competed May 20–21 with 11 other disabled riders for one of the six spots on the team, and knew that her focus and determination to be flawless in her performance were the only ammunition she had against her competition. Her success meant another woman, blind from birth and an excellent rider Green much admires, will not compete on the team. “She is a beautiful rider, tall and very accomplished. I just happened to be a little more accurate.”

Green will continue to prepare for the event by working with her choreographer and trainers, and trying to visualize the competition. She will be required to show a walk, freestyle and trot for 20 contiguous meters each, then do both a walk and canter in two 10-meter circles—one in each direction. Her program must be four minutes long, but no longer than four and one-half minutes.

“I have to really focus on what I will do, have a mental picture of everything that will happen,” she says. “And then, I have to be as close to perfect as I can.”