The University Record, December 21, 1998

Health System in the black and on the road to recovery

Editor’s Note: This is the last in a series of three articles describing how the U-M Health System has been affected by fundamental changes taking place in the U.S. health care industry over the past decade. The first article focused on the shift to managed care and the impact it had on the then-named U-M Medical Center in the mid-1990s. Last week’s story explained why academic medical centers are particularly vulnerable to the current health care cost squeeze. This final installment looks at how the Health System is changing and growing, so it can continue to provide the highest quality patient care in spite of continuing reductions in clinical revenue. This series originally appeared in the summer 1998 issue of Michigan Today.

By Sally Pobojewski

Health System Public Relations

|

|

|

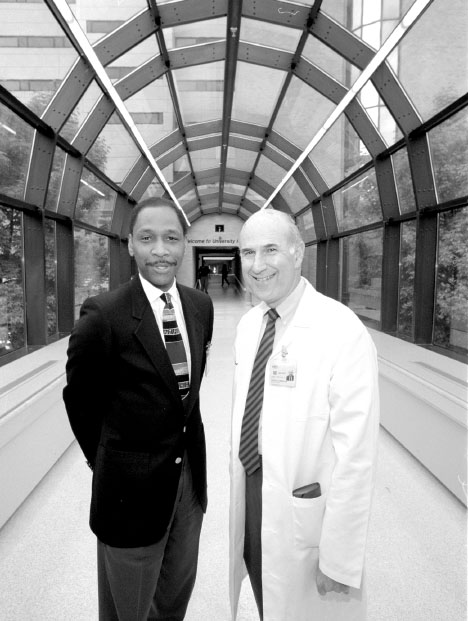

Larry Warren (left), executive director of U-M Hospitals and Health Centers, and Gilbert S. Omenn, executive vice president for medical affairs. Photo by Bob Kalmbach |

Changes in the Health System

The Medical Center has seen many changes in the two and one-half years since Lloyd Jacobs announced the layoff of 200 employees and elimination of more than 1,000 jobs as part of a three-year plan to cut expenses by $200 million.

For one thing, it has a new name–the University of Michigan Health System. There’s a new CEO–Gilbert S. Omenn, the University’s first executive vice president for medical affairs, joined the U-M in September 1997. And there’s a new organizational structure–all three U-M hospitals, 30 health centers, the Medical School and M-CARE are in one organization directed by Omenn.

Instead of a $16 million operating loss, the Health System ended FY ’98 with a $23 million gain from basic operations. A major initiative to expand and reorganize its primary care network has added 85 new primary care physicians to the faculty and 25 new outpatient health centers. Hard work and creative suggestions from employees have made it possible for the Health System to implement more efficient operating procedures and cut expenses by millions of dollars. The number of outpatient visits climbed to nearly 1.2 million last year, with inpatient admissions of 36,000. Business is so good that most of the nurses who were laid off in 1996 have been rehired and the Health System is looking for more nurses.

While its current financial status is excellent, Lloyd Jacobs, now chief operating officer for the Health System, cautions that the crisis is not over. “We’ve been successful at getting costs down and developing a cost-conscious culture,” Jacobs says. “We’re far more fiscally stable and competitive than we were two years ago. But we have to continue to respond to market pressures to reduce costs and we have to work harder to become more patient-friendly and improve our quality of care.”

|

|

|

The East Ann Arbor Health Center at the intersection of Plymouth and Earhart Roads. ‘Ambulatory care is the gateway to the entire health system,’ says David A. Spahlinger. ‘It’s important to make a good first impression, because patients have the freedom to walk out and take their business elsewhere.’ Photo by Bob Kalmbach |

Lorris A. Betz, former interim dean of the Medical School, adds: “There is a stronger sense of partnership between the Medical School faculty and the hospital administration, which has grown from the mutual recognition that we need each other to provide the highest quality patient care while supporting our academic mission in the face of a threatened loss of clinical revenue.”

The Faculty Group Practice

Physicians and administrators agree that one of the most important changes in the Health System was the formation in July 1996 of the Faculty Group Practice (FGP), which combined clinical activities of 15 separate departments into one self-governing organization.

“The Faculty Group Practice could be considered analogous to the federal government and the clinical departments to the states,” says John F. Greden, professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry and former chair of the FGP’s Board of Directors. “Ideally, they should work together. Before the Faculty Group Practice, departments often had competing, or at least not synchronous, missions and agendas, with little consensus on what we should be doing. Our current goal is to speak with one voice and improve the efficiency and quality of patient care.”

Since its creation, FGP has helped implement a centralized billing service, so patients no longer receive multiple bills from physicians in different specialties. Its 12-member board of directors determines the share of overall clinical revenue each department should receive. The organization has developed professional service standards that are being implemented throughout the Health System. These standards specify guidelines for everything from patient appointment scheduling to billing procedures and patient satisfaction surveys.

Customer service and quality of care are crucial to the success of the Health System’s new Ambulatory Care Division, according to David A. Spahlinger, FGP’s executive medical director. “Ambulatory care is the gateway to the entire health system,” Spahlinger says. “It’s important to make a good first impression, because patients have the freedom to walk out and take their business elsewhere.”

FGP’s professional service standards are an example of how managed care has generated positive changes in health care, according to John E. Billi, associate professor of internal medicine and of postgraduate medicine and health professions education. “Under managed care, physicians are held accountable and responsible for the quality of patient care they provide,” Billi says. “Patient satisfaction is one important measure of quality.

“Another development fostered by managed care is the creation of clinical practice guidelines, which are developed by physicians based on the results of scientific studies to specify the most appropriate medical care for a specific condition,” Billi adds.

Reinforcing this trend toward evidence-based medicine, the Health System is doing more to encourage clinical research–research that evaluates the effectiveness of new drugs or treatments for specific diseases on human subjects. This is a research area that many scientists say has been overshadowed by the Medical School’s national reputation as a leader in basic scientific research.

“Part of the obligation of an academic medical center is to take basic science advances from the laboratory through the steps required to produce an effective and practical treatment for patients,” Betz says. To do this, he and Omenn set aside $8 million to fund various joint research initiatives involving clinical and basic scientists in the Medical School. A $10-million Clinical Venture Investment Fund, established by the Faculty Group Practice and U-M Hospitals and Health Centers, also will be used to support new clinical research studies and other initiatives.

“What’s been most satisfying to me is seeing people recognize the need to work together to identify and solve our problems,” Jacobs says. “Everyone is working a lot harder now, but people are more engaged and committed to the future of the institution. We also are taking our responsibility to patients more seriously and realizing that the patients don’t work for us. We work for them.”

You can always drop us a line: [email protected].