The University Record, November 2, 1998

Faculty, others address issues raised by Boyer Report

By Rebecca A. Doyle

Is the University giving undergraduates the education and research experience they need and expect from a world class institution? Or is there something “broken” in the system that prevents undergraduates from learning how to ask questions, find answers and communicate results? Would a research experience for each student help fix that problem, or should faculty concentrate on becoming better teachers?

Is the University giving undergraduates the education and research experience they need and expect from a world class institution? Or is there something “broken” in the system that prevents undergraduates from learning how to ask questions, find answers and communicate results? Would a research experience for each student help fix that problem, or should faculty concentrate on becoming better teachers?

A morning panel of faculty members and an afternoon panel of policy makers addressed these basic questions and more detailed ones last week at “Research Universities and the Undergraduate: Designing Education for the 21st Century,” a full-day faculty forum held at the Ford Library. The forum was in response to a report issued in April by the Boyer Commission titled “Reinventing Undergraduate Education,” which prompted a storm of reaction from both media and faculty at the nation’s 125 research universities.

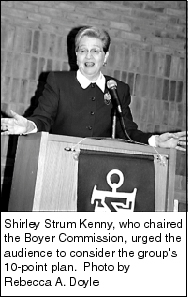

Shirley Strum Kenny, president of the State University of New York, Stony Brook, was the keynote speaker. Kenny, who chaired the Boyer Commission, urged faculty and administrators to look at the 10 areas and 56 recommendations the Commission made in its report.

“The report,” she said, “was mostly a call to arms. We’ve been talking about these issues for 30 years and haven’t fixed them yet. Now is the time.”

Kenny outlined the report’s 10-point plan, noting that undergraduate education in research universities should not try to duplicate either the curriculum or the mission of small liberal arts colleges. The freshman year of undergraduate work should “excite students, introduce them to research experiences and not repeat what has been covered in high school,” Kenny said. The report recommends freshman seminar courses for every student “in fields they’ve never studied before,” she continued. Also of major importance in the undergraduate years is learning the ability to communicate, and learning it differently than is presently taught.

When students have completed their education at whatever university level, Kenny noted, they must be able to write “down to someone who knows less about the subject than they do.” Too often, she said, students learn to write “up” to meet professors’ expectations and then lose the ability to communicate any results from their later research to a boss, the public or the media.

When students have completed their education at whatever university level, Kenny noted, they must be able to write “down to someone who knows less about the subject than they do.” Too often, she said, students learn to write “up” to meet professors’ expectations and then lose the ability to communicate any results from their later research to a boss, the public or the media.

Kenny also talked about interdisciplinary studies, use of technology in the classroom and the sense of community that should be present for undergraduate students.

Faculty members Lewis Kleinsmith, Bobbi Low, David Velleman, Donald Deskins, Ruth Scodel and Eliot Soloway served on the panel, discussing the report and their views of the role of the research university.

Kleinsmith, professor of biology, said that although he and most of the faculty endorsed the goals of the Boyer Commission in principle, it is “impractical to provide a research experience for every student, whether or not they want one.” He cited the drain on faculty time and the cost necessary to provide a quality research experience for each undergraduate student. “I would like to see the major point be quality,” he said, instead of mass producing research experiences that could become to students just one more requirement they need to fulfill to reach a goal.

Low, who is professor of natural resources, also noted that students are goal-oriented and tend to focus on what is required for graduation rather than what might lead to a “full life.” Some undergraduate students will specialize in certain areas and “some will become educated citizens,” she said. She noted that there is a need to overlap areas of expertise so that students can “draw inference from factual information and put that in context.”

Velleman, professor of philosophy, questioned the definition of research as opposed to inquiry. “If doing research is asking new questions and finding new answers,” he said, undergraduate students are not capable of doing research in his field. “Undergraduates are not capable of asking new questions until they know what has been asked before.” He noted that Aristotle, under the current U-M guidelines for tenure, would “be sunk.”

“The University has those who do research and those who teach,” said Deskins, professor of urban geography and sociology. “We would be dishonest if we said anything else.” He said that faculty can’t do both research and teaching because of a lack of resources and time, and the emphasis at the U-M is on research, not on teaching, because of the reward system (tenure), which looks at publication and research results as criteria.

Ruth Scodel, professor of Greek and Latin who directed the LS&A Honors Program for six years, said that the students she sees are “not reflective, they haven’t read” and that research, as faculty do it, “is not really what students need. Inquiry may be a very good thing; research we have to think about,” she concluded.

Eliot Soloway, professor of electrical engineering and computer science and of education, pointed to his work with K-12 students as an example of how inquiry and research lead to more engagement in the learning process. “These kids are asking questions. And if it’s their question, they take ownership, engage in discourse around those questions.”

The afternoon panel of University administrators and Washington policy makers was put together to address ways to achieve changes discussed in the morning. Instead, U.S. Rep. Vernon Ehlers talked about the importance of research in undergraduate education and ended with a “plea about curriculum—tie into the work that scholars are doing, center the work around the universe and get the answers out.”

President Lee C. Bollinger said that the U-M has done a lot in the past five to 10 years that improves the undergraduate experience. He cautioned against falling into “the traps that are in the air,” saying that higher education in the United States is “an enormous success story.”

“To say that higher education is sick and needs to be cured, or reformed—that’s a wrong attitude,” he said. “I’ve asked students here on campus what they like or don’t like, whether they are happy here. Nearly all of them say they are exceedingly happy with the education they are receiving here at the University.”

Bollinger said that he was concerned about the negative stereotype of faculty members, noting that most faculty are highly motivated and extremely good. He cited figures to support the idea of limited resources and noted that an education at the U-M is an extremely good bargain for undergraduates as well as graduate students. Education costs are extremely high, he said, and in-state tuition at the U-M is only $6,000 per academic year.

He questioned the seemingly accepted notion that large lecture classes are bad and that research is great. “Research is tedious, time consuming and for students to watch me do my research, or for me to discuss with a student all the research I am doing, is a colossal waste of time,” said Bollinger, who teaches an undergraduate course on the First Amendment.

He also cautioned faculty against being tradition-bound and putting too much emphasis on the past, and asked faculty to consider what he called “the great issues: Are we receptive to contemporary creativity? What will the effects of genetics and other scientific research be on artistic growth?”

Regent Olivia Maynard talked about the role pure research plays, but pointed out to faculty that there is much merit in the “role for transfer of research to the community. We are a public university supported by taxpayers, and we must honor that public support by asking how we can build on our current excellence without losing the value we have.”

National Science Foundation Undergraduate Science Adviser James Lightbourne echoed Maynard’s statement when he told faculty that there is a “need to engage research scientists in educational activity and to facilitate the exchange of ideas in the community.”

Bollinger answered later questions from faculty concerned about the U-M’s tolerance for mediocrity in teaching, but not in research, a view that was expressed more than once.

“I don’t believe that is our standard,” Bollinger replied. “I am not happy with that proposition.” Speaking especially about standards for younger faculty who are on the tenure track, he said, “We will make it clear that teaching is exceedingly important.”

The forum was sponsored by Sigma Xi, the Senate Advisory Committee on University Affairs, the U-M chapter of the American Association of University Professors and the Academic Women’s Caucus.

You can always drop us a line: [email protected].