The University Record, January 25, 1999

In celebration of Martin Luther King Jr.

Duderstadt chronicles role of activism in Michigan Mandate

By Jane R. Elgass

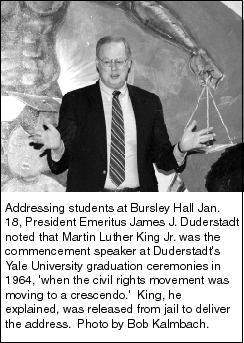

It was perhaps fitting that the individual credited with crafting the strategic approach the University would take in the late 1980s and early 1990s to enhance its diversity addressed a group of students in the Martin Luther King Lounge in Bursley Hall on Martin Luther King Day.

It was perhaps fitting that the individual credited with crafting the strategic approach the University would take in the late 1980s and early 1990s to enhance its diversity addressed a group of students in the Martin Luther King Lounge in Bursley Hall on Martin Luther King Day.

The U-M, Duderstadt noted, has in the past 10 years developed one of the most comprehensive programs in the nation, offering a broad array of learning experiences for all students. But it wasn’t always like that. Much of what is taken for granted by today’s students, he pointed out, was achieved as a result of student activism.

Since its inception, the U-M has been determined to serve all of the public, offer the opportunity of a college education to all regardless of economic class, gender, religion, race or nationality, Duderstadt explained, a stance that was challenged many times over the years. “Time and time again,” he said, “it took the action of students to awaken the University to this long-standing tradition.”

Tossing out such acronyms as BAM I, BAM II and UCAR, the former president provided a lesson in the recent history of U-M student activism, indicating that the time probably is right for a new era of activism with respect to challenges to affirmative action in the nation’s courts and legislatures.

With “civil rights on the front burner” in the 1960s, students launched BAM I (Black Action Movement) to force the University to recognize that it “was seriously underserving underrepresented minorities.” Joined by faculty, the activism resulted in changed policies and the University’s recognition of its social obligations to the greater society.

Activism resurfaced in the late 1970s, with BAM II, and while it gained attention, the focus was short-lived, Duderstadt said.

By the early 1980s, minority enrollment was declining and frustrated faculty of color were leaving the University.

Activism by the student-initiated Free South Africa Coordinating Committee forced the University to divest stocks held in companies doing business in South Africa in 1983.

Near the end of that decade, the U-M faced serious challenges. Enrollment of African American students stood at 4 percent and serious racial incidents were taking place on campus. BAM II and UCAR (United Coalition Against Racism), both multiracial groups, “pushed the University administration very hard [for changes].” This included the recognition of MLK Day and presentation of an honorary degree to Nelson Mandela, jailed in South Africa at the time.

By 1986–87, Duderstadt related, it was clear that students and others “were calling for a profound change in the nature of the University, and this would only occur with an organized effort.”

As provost and vice president at the time, Duderstadt brought together people from across campus to craft the Michigan Mandate, “a strategy that would embrace diversity as the cornerstone of excellence.”

Among the Mandate’s goals was a student body that would reflect the broader society, one-third students of color by the end of the 1990s.

The University undertook massive efforts and made major investments to reach out to prospective students and to make the U-M a place to which they would want to come.

Between 1986 and 1996, enrollment of students of color increased from 11 percent to 26 percent, Duderstadt said. When he stepped down as president in 1996, five of the University’s 10 senior officers were African American.

The University is “vastly more diverse today,” he said. “We can demonstrate that we became a better institution by the qualifications of our students and the reputation of our faculty. The majority of our students come here to be part of our diversity.”

The University is increasingly recognized as a national leader in diversity, but that status has a negative side. “As a result, we’ve become a target in the steps taken to halt such efforts in the last few years,” he said, citing legislative efforts in California and Washington state and legal challenges in Texas and at the U-M.

“The current generation nationally seems to have forgotten the commitments made by society in the 1960s and 1970s. At the U-M, the last several years have been characterized by apathy. Students are concerned, but not at the same level of intensity, not the same pressure.

“Is it time for that again?” he asked. “Yes. I’m convinced that American society cannot allow those commitments to backslide as a result of efforts by what I hope is a fairly vocal minority. I still care deeply about these issues, for the University and the broader society.”