The University Record, September 30, 1998

Careful daily care keeps special mice ready for research work

By Rebecca A. Doyle

They’re furry and furless, white, brown or black, and thousands of them are used at the University each year.

They’re furry and furless, white, brown or black, and thousands of them are used at the University each year.

Keeping track of the U-M’s research mice and caring for them is a job that requires time, patience, sterile procedures and lots of changes of food and water. The Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine (ULAM) rises to the challenge daily, caring for the 30,000 mice that are annually used by the U-M’s research staff.

Included in the total are special mice that are bred for their lack of immunity. Nude mice–so named because of their lack of hair–and other immunodeficient mice are of special importance to medical researchers who are trying to find out how cancer, lupus, psoriasis and other diseases can be controlled. Immunodeficient mice are specially bred rodents that have little or no built-in way to fight off foreign cells and therefore can readily accept cells from other animals.

Severely compromised immunodeficient (SCID) mice and nude mice present a special problem for caretakers, though. Because of their immune deficiency, they must be protected from bacteria and diseases since their bodies can’t fight them off.

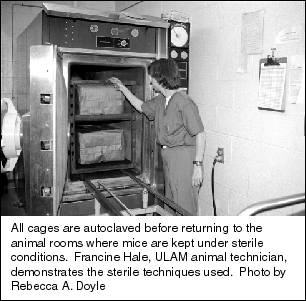

Because of their value to researchers, Francine Hale, ULAM animal technician, and ULAM Director Dan Ringler developed a number of years ago a procedure to make sure that immunodeficient mice were disease-free. Sterile procedures are now used with all mice, Ringler says, and researchers can use the mice without worrying about whether the results will be affected by an outside disease.

Keith Bishop, assistant professor of surgery and of microbiology and immunology, uses SCID mice in his study of transplant rejection. “These are incredibly informative mice. We can select a specific population of cells and put them in these animals to ferret out mechanisms by which cells reject transplanted cell colonies. The results are not complicated by the animal’s immune system,” he says. Bishop’s research has been funded by the National Institutes of Health for nine years.

Blake J. Roessler, associate professor of internal medicine and of pharmaceutics, also uses SCID mice in his search for new techniques in gene delivery systems for treatment of skin diseases. Because of their special genetic makeup, mice used in his study do not reject human skin cells.

“One of the advantages of this method is that the skin grafted to the mice has no nerves, so the mice feel no discomfort. We use between 25 and 100 mice each year,” he notes. “We have had an excellent relationship with ULAM. Their care and oversight in the nude mouse facility is outstanding.” Roessler is in the second year of an NIH-sponsored project with a five year contract. “We are making steady progress,” he says.

Kenneth J. Pienta, associate professor of internal medicine and of surgery, uses nude mice in testing chemotherapeutic agents in prostate cancer. Using cell lines from donors, the nude mice grow tumors that researchers in the lab can follow to see how they metastasize, how the malignant cells travel from one part of the body to another. Using nude mice eliminates the chance that the animal’s own immune system might attack foreign cells.

Susan Brumfield, research associate in Pienta’s laboratory, says the her experience with ULAM has been very good.

“They take good care of the animals and have a licensed veterinary technician who checks to see if there are any problems and alerts me right away,” she says. “It helps a lot that they are so observant.”

Pienta’s research is funded by a SPORE grant and he began transplanting human cells in 1996. “We have several different cell lines growing in culture now and will use them to research tumor growth, how they are affected by hormones and the time between cell introduction and tumor appearance,” Brumfield says.

Theodore S. Lawrence, professor of radiation oncology, uses immunodeficient mice to grow human tumors, to measure tumor response to chemotherapy and radiation therapy, and to test new therapies. “We test the therapy on mice before we conduct clinical trials involving humans. If we used regular mice, with normal immune response, they would reject the human tumor,” Lawrence says. “Currently, we are working on a new approach using gene therapy, which has never been done in humans before.”

Nude mice are bred specifically for research and are descended from a mouse exposed to radiation in Europe many mouse generations ago. In examining the mouse, researchers discovered that a genetic abnormality left it not only bald but with very little immune response. The hairless mouse became an ideal subject for cell transplants and in vivo (in living animals) growth of cells because it would not reject the cells. Subsequently other mice that were not hairless but had some of the same immune system deficiencies were bred specifically for research purposes.

Hale has worked at ULAM for 15 of her 30 years at the University, and has taught the procedures she and Ringler developed to other animal technicians at the University. The U-M is well known for its procedures, which have been adopted in many other institutions. Originally nude and SCID mice had an extremely short lifespan because of their inbred deficiency. With the sterile techniques that ULAM now uses, they reach nearly the normal lifespan of regular mice–two years.

You can always drop us a line: [email protected].