The University Record, November 16, 1998

Bowen discusses race, admissions

By Rebecca A. Doyle

In the mid-1950s, Vernon Jordan attended DePauw University as an undergraduate, where he was the only Black student, William G. Bowen told an overflow audience last Thursday. Jordan roomed with two white students who, according to Bowen, said to him after a few weeks, “We have come to the most astonishing conclusion. You are just like us.

In the mid-1950s, Vernon Jordan attended DePauw University as an undergraduate, where he was the only Black student, William G. Bowen told an overflow audience last Thursday. Jordan roomed with two white students who, according to Bowen, said to him after a few weeks, “We have come to the most astonishing conclusion. You are just like us.

“You fall asleep over your desk at night. Your mother sends you cookies.”

Jordan later related the incident to Bowen, saying, “Do you think those guys learned anything from the fact that I was at DePauw? I did.

“I spent most of the rest of my life in a predominantly white environment,” Jordan told Bowen “and my ability to function effectively in that environment owes so much to those undergraduate days at DePauw.”

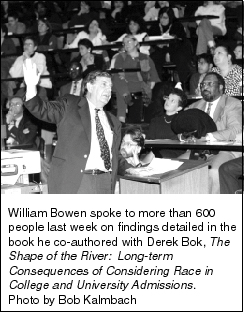

Bowen spoke about his book, The Shape of the River: Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions, as part of Dialogues on Diversity, a Universitywide initiative that explores diversity in all its forms. He is former president of Princeton University.

The anecdote about Jordan, Bowen said, is backed up by data he reveals in his book, co-authored with former Harvard University President Derek Bok.

That data show that higher education institutions holding two basic objectives as part of their educational mission will serve their mission better by choosing to admit a diverse student body. Those objectives are 1) ensuring a diverse environment that will provide students with skills for living in a pluralistic world and 2) preparing a larger number of minority students to enter professional schools and assume positions of civic and community leadership.

Data from studies done in 1976 and 1989 of 28 highly selective colleges and universities form the basis for the conclusions Bowen and Bok have drawn.

“How much difference does it make,” Bowen asked, “to have a diverse environment in higher education?” How important is it to students to have learned at that level to get along with others across racial lines as part of their college education?

Bowen said that, to him, the most significant responses in the study of 45,000 students were those given by students who had graduated a number of years before and who could correlate their college experience with their career experiences.

“The interesting thing, I think, is that between 1976 and 1989, there are big bump-ups in the percentage of both [African American and white students’ positive responses],” Bowen said.

“So certainly the students who were actually there thought that it was a real benefit to them in their education.”

In addition to that data, Bowen’s figures show that in highly selective schools—where the admissions policy is under attack—not only do students value the diverse environment, but African American graduates who choose careers in law, medicine, business and academia are more likely than their white counterparts to contribute to their communities in social service activities.

Bowen ended the body of his talk with four points that are the conclusions he and Bok have reached as a result of their study of the data.

• The “fit” hypothesis, also referred to as making the beneficiaries into the victims, which argues that Black students who have lower SAT scores will not be able to compete or fit in with students who have average SAT scores of 1300, and will not complete their education.

“For the first time, we were able to test that hypothesis with large numbers of people,” Bowen said. “Of the Black students who had SAT scores in the 1,000–1,099 range, the ones who went to the top-level schools showed exactly the opposite of what this hypothesis predicts.

“The pattern is relentless,” Bowen said. The data from the studies show that Black students with SAT scores of between 1,000 and 1,099 had the highest graduation rates when they attended the most select of the schools studied, and graduation rates decreased slightly for the second- and third-tier schools.

“The fit hypothesis really should be given a rest because it is not supported by any of the data,” Bowen said.

• Eliminating the consideration of race in admissions would have a very substantial impact on Black enrollment at the academically select schools.

Bowen presented data that show the top colleges and universities are being very particular in choosing students from the applicant pool. “High SAT scores are not a guarantee of admission for anybody, whether you are white or Black,” Bowen said.

“If we were to eliminate race in admissions, what you find in this actual assessment of impact is that in the most selective schools the actual minority enrollment of about 8 percent would fall to about 2 percent,” Bowen said. “Overall, the actual enrollment [of minority students] would fall to about half and in professional schools the impact would be even greater.

“We’re talking about an issue of enormous consequence in terms of what the student bodies would look like and the opportunities that these schools would offer.”

• Using socio-economic status instead of race as a factor in admissions decisions would not achieve the diversity while maintaining the same academic standards.

“There are no easy answers, no simple alternatives,” Bowen said.

• Looking at all the results, the most basic question is how merit is defined. “Do we believe people should be admitted based on merit? Absolutely,” Bowen said. But defining merit is a matter that requires individual attention to the qualities of each individual, not just scores, he said. “It seems to me one of the serious errors is to think of merit as implying a process of awarding applicants for what they have already accomplished.

“We should ask ‘what are we trying to accomplish?’ and select people who contribute the most to what we are trying to accomplish,” Bowen said. We should judge merit by the objectives of the institution, and if the objective is to create a rich learning environment, then race is truly a relevant factor. If we are trying to create a society that is less stratified than the one we live in today, then obviously race is a factor along with a host of others.

“To turn back, look away from the progress that has been made, what would that do to our collective sense of hope and optimism and progress?

“I think not very good things,” Bowen concluded.

Bowen answered questions from the audience on such issues as job competition between Black and white applicants, how he could justify denying admission to a white student, and his opinion of how admissions officers should select applicants from the large pool they are responsible for—each sometimes handling as many as 1,000 applications.

Bowen said institutions should look at “which student will bring more to the enterprise. It is simply the case that many African American applicants bring more to the table with the contributions they have to make.”

One of the great mistakes is to combine admissions data with work or job data, Bowen said. “The debate of affirmative action is hurt, not helped, by putting it all together.”

Recruiting students is not something that should be undertaken lightly, Bowen asserted. “Spending money on selecting students is money well spent,” he said. “We are obligated to give the selection process the resources it needs to choose individuals in a certain way, then to look at the results and continually evaluate the process.”

You can always drop us a line: [email protected].