Letters from F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Gen. George Armstrong Custer and Depression-era Public Enemy No. 1 John Dillinger join U-M’s 1817 original charter and the papers of Detroit auto magnates in the Bentley Historical Library’s collections, which continue to grow, setting in motion a curious dynamic.

That’s because more historical collections draw more researchers, which in turn draw more donated collections. It’s a process that helps the Bentley fulfill its mission to collect important documentation on the history of both Michigan and U-M — and make it available to scholars and the public, says Francis Blouin.

Emma Hawker, assistant archivist, returns a box containing historical records to the stacks at the Bentley Historical Library. Photo by Martin Vloet, Michigan Photography.

Bentley director since 1981, Blouin this month returns to duties as professor in the Department of History and School of Information. Terrence J. McDonald, former dean of LSA, is the Bentley’s new director.

“It’s really a major selling point of the Bentley Library, we’ve integrated many prominent people and institutions, so the region’s story can be told more fully,” Blouin says.

For example, the story of Michigan seed magnates the Ferry family connects to the origins of the Detroit Institute of Arts, and Detroit’s boom years. “One thing builds on another,” Blouin says, adding that related collections also draw researchers.

Tom Sugrue, a University of Pennsylvania professor and administrator, says the Bentley was indispensable for research on his book “The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit.”

“I was the first historian to leaf through the crumbling pages of cantankerous conservative editor Floyd McGriff’s Detroit neighborhood newspapers, just as the library was microfilming them,” Sugre says. While he’s worked in dozens of archives, “few are as professional, well-run, and user friendly as the Bentley,” he says.

Since its founding in 1935, the library has amassed more than 50,000 linear feet of archives and manuscripts, 90,000 printed volumes, 1.5 million photographs and other visual materials, more than 10,000 maps and nearly 60 terabytes of digital content on the history of the state and the university. Those archives include growing digital resources and possibly social media records.

Preserving U-M history

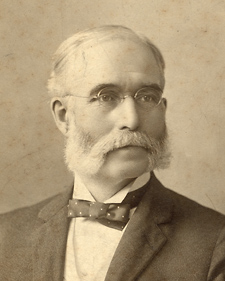

U-M’s Ferry Field was named for Ferry Seed Co. Founder Dexter Ferry, pictured above. Ferry’s grandson donated the family’s papers to the Bentley Historical Library. Photo by Courtesy Bentley Historical Library.

To archive historic material about university departments and their work, Bentley staff seek material from entities that have had a significant impact in shaping their respective disciplines. “We rely on supporters on campus to help us identify outstanding faculty likely to have retained good documentation,” says Bentley Archivist Brian Williams.

One standout collection that meets this criteria is the John W. Aldridge papers. It focuses on his time as a director of the Hopwood Awards Program and as an English professor on campus. “What really stood out was his personal correspondence, which included many of the 20th century’s most significant writers: Arthur Miller, Norman Mailer, John Updike, Saul Bellow and Kurt Vonnegut, just to name a few,” Williams says.

Aprille McKay, assistant archivist, says Bentley staff regularly seek records including tenure, promotions and correspondence files from deans, and input from individuals ranging from deans to leaders of student organizations on key developments and individuals.

The overwhelming bulk of materials collected by Bentley staff to date are on paper. “Our records are not digitized for the most part. The public can come into the library to access them,” McKay says. The website presents finding aids, basically folder numbers assigned to inventories of information by subject, to guide in-person paper searches at the library. Documents presented to the Bentley are placed into acid-free folders and stored in archival boxes in secure, climate-controlled stacks. Oversized materials are housed in special boxes and architectural drawings are also stored in special architectural folders. Information about how to prepare paper records is at www.bentley.umich.edu/uarphome/manual/boxrecs.php.

Online university records

The public can access several online records pertaining to U-M at the Bentley website: bentley.umich.edu. There are links to exhibits and special projects ranging from Presidents of the University of Michigan to The History of Diversity at U-M, and the Faculty History database, a project of Jim and Ann Duderstadt. The Bentley Image Bank, also available on that site, offers access to historical photos related to U-M.

As part of the U-M Library system, the Bentley helps maintain the Hathi Trust digital repository and research management tool, with access to U-M publications ranging from yearbooks to conference programs. Associate Archivist Nancy Deromedi, who oversees digital archives at the Bentley, says a large digitization project is underway involving archival audio materials. The library holds thousands of recordings in multiple formats ranging from tape reels, discs, wire recordings and cassette tapes. They include interviews, oral histories, musical performances and radio broadcasts. In 2012, the library started working toward digitally preserving a selection of reel-to-reel and cassette tapes from these materials. Recordings from more than 100 collections from the University Archives and the Michigan Historical Collections were chosen to make the contents digitally available for researchers. Files for each tape will include a wav preservation file, wav production file, and an access mp3 file for streaming. Collections include the Men’s Glee Club, TV’s 60 Minutes reporter and alumnus Mike Wallace, Ann Arbor activists John and Leni Sinclair, Michigan Radio WUOM, and the Canterbury House records.

Deromedi says it’s a challenge to adapt to digital content because technology and its uses continue to change at a rapid pace. “We have been proactive in appraising and developing a solution to archiving websites. The digital curation staff has worked through the issues in collaboration with Bentley division heads and with the help of university webmasters. Social media, however, has added a new dimension to how units are creating and disseminating content,” she says.

The Bentley is seeking to raise awareness among academic and units about maintaining their individual digital archives. A document created by Bentley staff, “Guidelines for the Selection of Sustainable, Preservation-Quality File Formats,” addresses format sustainability and provides recommendations to units. It is at www.bentley.umich.edu/dchome/resources/formats.php. “Digital content presented to the library undergoes virus scans and other processing, before being ingested into Deep Blue, U-M’s institutional repository,” Deromedi says. Collections held there include class schedules from the Office of Registrar, oral interviews as part of the Women in Science and Engineering Program and material documenting the East Quad Memory Project. These collections are at deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/65133.

Getting to know you

Establishing relationships with those who hold historical papers can lead to donations. Nearly 20 years ago, Blouin established a relationship with Stanley Kresge, heir of retailing pioneer Sebastian Kresge, founder of Kresge department stores and Kmart. The goal was to secure for the Bentley’s collections the family’s papers concerning its retail empire.

“He agreed to meet with me in his office in Troy, he wanted to know a little bit about the library. I told him what we were trying to do,” Blouin says. “He said it would be interesting to do this but he would have to give it some thought.”

Blouin and Kresge agreed to talk every nine months or so. “He always agreed to meet and we’d have a pleasant chat. He’d show me some of the historical papers in his office, but would never quite commit to donating them,” Blouin says.

Finally, Kresge made a decision. “On one of my later routine stops, he said, ‘OK — Take them.’”

Dexter Ferry, whose family founded the successful Ferry Seed Company and for whom U-M football’s historical Ferry Field was named, made it known that he was looking for a home for his family’s papers. Ferry began speaking with various suitors, and interviewed Blouin at the Ferry family home in Grosse Pointe. He asked what would happen if he wanted some of the papers back, after they were donated.

“I told him he’d have to fill out a form to request the material, and would eventually have to return it. He said, ‘You and I think the same way, we like things to be tidy,’” Blouin recalled. Ferry donated the papers to the Bentley.

Auto focus

Bentley Archivist Leonard Coombs collects documents for the Michigan Historical Collections at the library. Staff focus on topical areas with the greatest long-term value for historians, students and other researchers.

“One of our top collecting priorities is to document the decline and rebirth of Michigan’s auto industry,” Coombs says. The Bentley has collected personal papers of industry leaders including most recently Robert Stempel, former chairman of General Motors; inventors and innovators including Stanford Ovshinsky, inventor of battery technology and other innovations; auto dealers including Hamtramck’s Woodrow W. Woody; and auto journalists and researchers including Jim Dunne of Popular Mechanics and David E. Davis of Automobile Magazine.

The Bentley’s Digital Curation Division also has collections of Web documents from the General Motors and Chrysler bankruptcies. “The Bentley Library has built our collections entirely through donations of manuscripts and archives. We do not purchase collections, but depend on the good will of the people and organizations who have created the historical record of our state,” Coombs says.

More persistence

Williams offers another example of how persistence pays, to grow the library’s collections. U-M’s 298th General Hospital Unit, which operated like a M.A.S.H. unit during World War II, was staffed by faculty and staff from the Medical School and University Hospital. Harry A. Towsley served with the 298th and was the unit historian. “As early as 1946 staff from the archives wrote to Towsley to express interest in the material. He was interested in placing the material in the archives but wanted to wait until he was finished using the material,” Williams says.

Periodically, archives staff would remind Towsley of the Bentley’s interest, only to receive a polite response that he was using the material for an article, or wanted it on hand for a reunion of 298th personnel he was hosting. Then, in 1985, the first installment of 298th material arrived at the Bentley. The rest arrived in the early 1990s. Included with the material was a folder containing all of the periodic appeals from the Bentley.

“Today the Harry A. Towsley papers, which contain the 298th material, are one of the most heavily used collections at the Bentley. It just took patience and almost 40 years for it to arrive,” Williams says.

Meanwhile, new collections keep arriving. A notable recent acquisition is the papers of Douglas Roby, U.S. representative to the International Olympic Committee from 1952-84. “His papers provide great documentation of the issues of international sport and the politics of the Olympics in a very contentious period, when sport reflected Cold War tensions and other societal issues,” Coombs says.