Surface appearances can be so misleading: In most forests, the amount of carbon held in soils is substantially greater than the amount contained in the trees themselves.

If you’re a land manager trying to assess the potential of forests to offset carbon emissions and climate change by soaking up atmospheric carbon and storing it, what’s going on beneath the surface is critical.

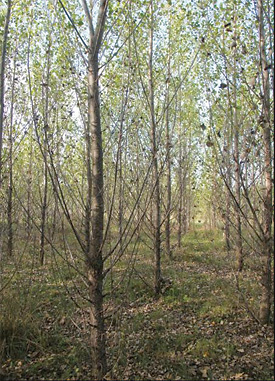

Forest plantations established on formerly nonforested land, like this experimental poplar stand in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, accumulate soil carbon that helps to offset carbon emissions and climate change. Photo by Ray Miller.

But while scientists can precisely measure and predict the amount of above-ground carbon accumulating in a forest, the details of soil-carbon accounting have been a bit fuzzy.

Two U-M researchers and their colleagues helped to plug that knowledge gap by analyzing changes in soil carbon that occurred when trees became established on different types of nonforested soils across the United States.

In a paper published online April 1 in the Soil Science Society of America Journal, they looked at lands previously used for surface mining and other industrial processes, former agricultural lands and native grasslands where forests have encroached.

U-M ecologist Luke Nave and his colleagues found that, in general, growing trees on formerly nonforested land increases soil carbon. Previous studies have been equivocal about the effects of so-called afforestation on soil carbon levels.

“Collectively, these results demonstrate that planting trees or allowing them to establish naturally on nonforested lands has a significant, positive effect on the amount of carbon held in soils,” said Nave, assistant research scientist at the U-M Biological Station and in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Nave is lead author of the paper.

Large and rapid increases in soil carbon were observed on forested land that previously had been used for surface mining and related industrial processes. On a post-mining landscape, the amount of soil carbon generally doubled within 20 years of mining termination and continued to double every decade or so after that.

The changes after cultivated farm fields were abandoned and trees became established are much subtler, though still significant. This type of tree establishment — which has been widespread in recent decades in the northeastern United States and portions of the Midwest — takes about 40 years to cause a detectable increase in soil carbon.

But at the end of a century’s time, the amount of soil carbon averages 15 percent higher than when the land was under cultivation, with the biggest increases (up to 32 percent) in the upper two inches of the soil.

In places where trees and shrubs have encroached into native grassland, soil carbon increased 31 percent after several decades, according to the study. That type of incursion is occurring throughout the Great Plains, from the Dakotas to northern Texas, largely due to suppression of wildfires.

Most of the organic carbon in forest soils comes from the growth and death of roots and their associated fungi, he said.

Knute Nadelhoffer, director of the U-M Biological Station and a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, was a co-author of the Soil Science Society of America Journal article.