More online

Watch Kamal Sarabandi discuss how his millimeter-wave radar system could detect weapons >

In the weeks after the Connecticut school shooting, as the nation puzzled over how it happened and what might prevent it from happening again, Kamal Sarabandi was listening to the news. Talk turned to giving teachers guns, and he paused.

“I said, there must be a better way,” Sarabandi recalled.

Then he had an epiphany. Sarabandi is the Rufus S. Teesdale Professor of Engineering and professor of electrical engineering and computer science. His specialty is remote sensing — detecting objects and gathering information from a distance. And for several years, ending in mid-2012, he was funded by the U.S. Department of Defense to tweak a type of radar, not too different from the kind police use to nab speeders, and use it to find weapons and bombs concealed on a person’s body.

The funders envisioned it for military uses. But after Newtown, Sarabandi wondered if his research had homefront applications. Maybe his millimeter-wave radar system could flag weapons on their way in to busy places where they’re not allowed.

“Schools, airports, stadiums or shopping malls — wherever there is a large number of people that you want to protect,” Sarabandi said.

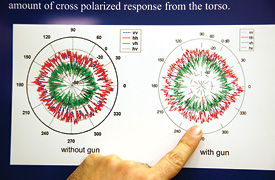

Kamal Sarabandi points to the difference in the visual response from the radar of a subject with a gun compared with one without a gun. Photo by Marcin Szczepanski, College of Engineering.

It could work from a football field away, Sarabandi says, and take less than one second per person. That’s a lot quicker and more convenient than a metal detector, he adds.

The new technology isn’t in the radar system itself, which, like all radar, senses objects by sending out radio waves and listening for the signals that bounce back. Sarabandi’s particular millimeter wavelength is used today in collision-avoidance systems in cars, in satellite communications and in military targeting and tracking, for example.

Sarabandi paired it with Doppler radar signal processing to pick out the signature of a person walking in the noisy radar scene. Then he uses a technique called radar polarimetry to essentially squint at the signal coming from the pedestrian’s torso and identify the telltale glare that a metal object hidden there would cause.

He hasn’t tested the technology on people, or people with real guns. But he has done computer simulations. He has also conducted experiments in an echo-reducing chamber with a mannequin hiding a nail-studded block of wax under a leather jacket. The nail block stands in for a makeshift explosive.

Here’s how the concept works: Doppler radar, famous for its weather and speed-trap applications, uses the Doppler effect to measure an object’s speed. It can tell a meteorologist how fast a storm is approaching, for example. Sarabandi used it to identify what parts of the reflected signal were coming from, say, the limbs and what part was coming from the torso of a human walking.

To do this, he first attached motion-capture electrodes on the limbs and torsos of several human subjects and had them walk around in the U-M 3-D lab. He used the recordings of their motions to make true-to-life animations. Then by simulating their Doppler radar reflection over time, he identified a general pattern that he could program a computer to recognize. It’s a spiky graph to the untrained eye, but to Sarabandi, it represents “the DNA of walking.” To confirm that it was specific to humans, he compared it with the signal from a walking dog.

Once he knew he could pick out the people, he zoomed in on their torsos — a sweet spot for two reasons: People often hide weapons there, and it’s a relatively smooth backdrop against which to see something out of the ordinary.

Sarabandi’s idea would be to scan a large group of people from a distance. Then security guards could watch flagged individuals more closely or pull them aside for scans with more sensitive devices.