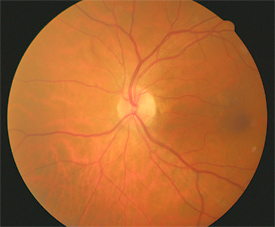

By digitally photographing the tiny, hair-like blood vessels in the back of our eyes, researchers now can look directly at how small vessels like those that bring blood to the heart respond to air pollution.

New digital photos of the retina revealed that otherwise healthy people exposed to high levels of air pollution had narrower retinal arterioles, an indication of a higher risk of heart disease.

Researchers are examining digital photos of tiny blood vessels in the eye to investigate how the vessels respond to pollution. Photo courtesy of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.

Previous studies linked pollution to heart disease. The new study, published last week in PLoS Medicine, is the first known to examine relationships between pollution and extremely tiny blood vessels, called the microvasculature, in humans, says Sara Adar, research assistant professor at the School of Public Health. Adar did the work while an assistant professor at the University of Washington School of Public Health.

Researchers found that participants with short-term exposures to small amounts of pollution had the microvascular blood vessels of someone three years older, and people with long-term exposures to high pollution had the vessels of a person seven years older. Adar says that “such a change would translate to a 3 percent increase in heart disease for a woman living with high levels of air pollution as compared to a woman in a cleaner area.”

Retinal vessels are examples of the very small vessels that exist in the heart and throughout the body. The ones in the eye are unique, however, in that we can see them, take pictures of them and measure them directly in people without needing scalpels, probes or anesthesia, says Dr. Joel Kaufman, professor of medicine and occupational and environmental health sciences at the University of Washington, Seattle, and senior author. “The fact that this study identified a relationship between microvascular width and air pollution exposures provides a strong potential link between the epidemiological observations of more cardiovascular events like fatal heart attacks with higher pollution exposures and a verifiable biological mechanism.”

Even though pollution levels in the study were generally below the level that the EPA considers acceptable, these levels still appeared to negatively affect the tiny blood vessels, which are about the width of a human hair, Adar says. Though the vessels only narrow by about 1/100th the width of a human hair, this could have important health consequences if all of the microvasculature in the body is affected in the same way, she says.

In order to establish a causal relationship between air pollution and heart disease, scientists must demonstrate a plausible biological mechanism between exposure and the disease, Kaufman says. This particular study provides compelling evidence in living people of the visible biological effect of air pollution in a pathway related to heart attack, stroke or other vascular events.

Going forward, Adar says it’s important to study the effects over time.

“Another exam, which is currently underway in these same people, will allow us to see if we can find changes in these vessel diameters over time as a function of air pollution,” she says. “If we can, that will give us even more evidence that air pollution causes this vessel narrowing.” Adar says that study could produce results in as little as two years.