Scientists at the Comprehensive Cancer Center have identified a gene that controls the ability of adult stem cells to self-renew, or make new copies of themselves, throughout life.

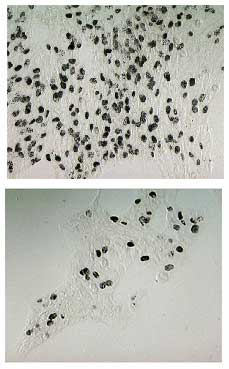

In a series of extensive cell culture and animal studies, scientists discovered that a gene called Bmi-1 was required for self-renewal in two types of adult stem cells—neural stem cells from the central nervous system and neural crest stem cells from the peripheral nervous system. In a previous study, other U-M scientists found that Bmi-1 also was necessary for continued self-renewal in a third variety of blood-forming or hematopoietic stem cells.

“So far, we and our colleagues have studied three important types of adult stem cells, and Bmi-1 appears to work similarly in every case,” says Sean Morrison, assistant professor of internal medicine in the Medical School and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) investigator. “This raises the intriguing possibility that Bmi-1 could be a universal regulator controlling self-renewal in all adult stem cells.”

The study of Bmi-1’s role in central nervous system stem cells and neural crest stem cells from the peripheral nervous system was published Oct. 22 in Nature’s advance online edition.

Co-first authors are Anna Molofsky, a student in the Medical School, and Ricardo Pardal, research fellow. Previous U-M research on Bmi-1 and hematopoietic stem cells was conducted by In-Kyung Park, research investigator, and Dr. Michael Clarke, professor of internal medicine. Results from that study were published in Nature April 20.

Unlike embryonic stem cells, which exist for just a few days in the early embryo, various types of adult stem cells remain in many tissues throughout life. When adult stem cells divide, they give rise to more stem cells, in addition to mature cells that replace dead or damaged cells in the body. So, the ability of adult stem cells to divide throughout life is necessary for the maintenance of adult tissues.

Most cells in the body are programmed to stop dividing after a limited number of cell divisions, but adult stem cells and cancer cells have the ability to continue making identical copies of themselves for long periods of time, if not indefinitely. Exactly how they do this has remained a mystery—one that scientists all over the world are trying to solve.

“This paper defines one of the mechanisms that make stem cells special,” Morrison says. “We now know that Bmi-1 is an important part of the mechanism used by stem cells to persist through adult life. Certainly there are other genes involved and we need much more research to fully understand the process, but Bmi-1 is a major key to unlocking this important mechanism of self-renewal.”

Since cancer cells share the secret of self-renewal with adult stem cells, Morrison says his research “raises the possibility that inappropriate activation or over-expression of Bmi-1 in stem cells could lead to uncontrolled growth and cancer.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Searle Scholars Program, HHMI, U-M Medical Scholars’ Training Program, and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology.

In addition to Clarke and Park, Dr. Toshihide Iwashita, research fellow, also collaborated on the study.