The University Record, December 13, 1999 By Joanne Nesbit

News and Information Services

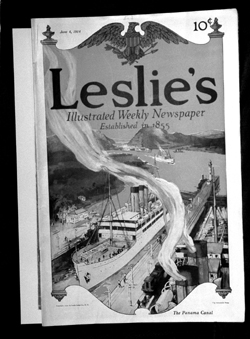

After 96 years, American involvement in the Panama Canal will end Dec. 31, the latest chapter in a 400-year saga of canal proposals and projects outlined in the latest exhibition at the Clements Library.

From Columbus and other explorers of the 15th and 16th centuries to blood-thirsty pirates, colonists and land speculators to gold seekers, revolutionaries, brilliant scientists and civil engineers, the story of the Panama Canal is one of scandals and successes, all documented at the Clements by letters, photos, hand-written accounts, political cartoons and news magazines.

“The Isthmus of Panama was the first potentially practical passageway between East and West to be discovered,” explains John Dann, director of the Clements Library. “Even before Magellan, there was talk of building a water route across the Isthmus. The first 350 years of Panama Canal history was largely one of grand dreams and disappointing realities. The more serious the projects became, the more elusive the goal. Finally, under the forceful leadership of Theodore Roosevelt, the United States rose to the challenge and produced what remains to this day one of the engineering wonders of the world.”

As early as 1597 a map of the Panama region suggested that a “ditch” between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans would be an easy project. Such maps, Dann says, underestimated the difficulties of the terrain and would continue to mislead distant government officials and entrepreneurs for centuries.

The 1848 California Gold Rush attracted thousands to the West Coast, but the only routes available were across the Plains or around Cape Horn, both dangerous and difficult. Once news of the precious yellow metal got out, ships began transporting men to Nicaragua and Panama where they would disembark and travel overland to the Pacific coast, and then re-board a ship for passage to California. “The earliest Forty-Eighters and Forty-Niners encountered difficult conditions as they crossed Panama by canoe, footpaths and mountainous terrain,” Dann says. “Although the foliage, birds, animals and native people were exotic, and the country beautiful, disease, crime and profiteering claimed many victims. By the early 1850s, railroads eased the journey, but the need for a canal became obvious.”

Mountains were removed, as were huge quantities of rock and dirt. The terrain was unstable and subject to frequent slides, burying equipment and taking lives, and causing long construction delays. From 1906 until 1914, tens of thousands of workers cut the canal across the Isthmus, bringing the project to completion five months ahead of schedule and well under budget.

But what does the future hold for the Panama Canal, once the U.S. relinquishes control? Will Panama resist pressure to develop the land and lakes that enables the delicate hydraulic system to operate? Will the Panama Canal be rebuilt to accommodate larger ships? Will a sea-level canal be built there, or at one of the other routes that were abandoned when the Panama site was chosen? These questions, Dann, says remain open and will be affected by such unpredictable factors as oil prices, ecological concerns, and both international and domestic politics.

The Canal is essentially unchanged since its construction at the beginning of the century. But Dann envisions a new chapter in the Canal’s history, “possibly with all the drama and international intrigue of the past 500 years.”

The Clements Library in large part owes its existence to the Panama Canal project. William L. Clements, a graduate of the U-M’s first Engineering School (1882), designed and manufactured cranes and steam shovels in Bay City. The Panama Canal project created an unprecedented need for such equipment and Clements’ factory was in high gear between 1904 and 1915. The business provided him with the extra personal income needed to put together one of the greatest collections of Americana in the world, which he donated to the U-M.

“The Panama Canal” continues at the Clements Library through February, and can be viewed 1–4:45 p.m. Monday–Friday.

Additional information about the “hand-over” of the Canal can be obtained from the Gerald R. Ford Library by contacting David Horrocks, 734-2218, ext. 222. Most of the negotiations for the exchange of the Canal were made during Ford’s administration.