The University Record, August 16, 1999

Use of primates in research focus of demonstration, media briefing

By Rebecca A. Doyle

In anticipation of the Aug. 12 visit from the activists crossing the country on the Primate Freedom Tour, Dan Ringler faced microphones and cameras last week to tell journalists the U-M side of the story and to clarify the U-M’s position and his own regarding primate research specifically and animal research in general. Ringler heads the Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine (ULAM).

Primates make up less than one-tenth of a percent of the research animals at the U-M, Ringler said, and are only used as a “last resort—when there is no other way to get the results. Primates are the closest species to humans, and we cannot by law use humans in this research.” Primates used in the U-M studies have been bred in captivity and have not been taken from the wild.

Ringler also told reporters that he believes, as do those at the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the National Kidney Foundation and other organizations, that “animal research is the only way to make rapid progress in treating these diseases.”

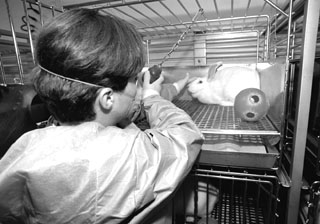

He also answered questions from reporters on specific research projects and led a tour through the facility to show reporters some of the research animals.

Asked whether any of the animals suffer painful procedures, Ringler responded that occasionally it was necessary, as when testing drugs for pain relief. The only current study he recalled in this area, however, is one that tests for sensation by putting an animal’s tail in warm water and measuring the length of time it takes the animal to withdraw its tail.

In another current study, primates are used in research on drug addiction. Ringler explained that scientists are testing how drugs react within the brain, the interaction of molecules of the drug with receptors in the brain. Drug screening is done later to find substitutes for the addictive drugs. “This kind of study requires primates,” he said. The procedure does not work in other animals, such as rodents.

Ringler pointed to results of other studies in the Medical School’s Department of Pharmacology that have led to the development of four to six drugs that now are used extensively in heart attack cases.

In general, animals are treated much as if they were human when pain is involved, he noted. “If a human would receive a pain-relieving drug for the procedure, then we would also give that drug to the animal,” he said. “If the procedure is something we would be able to do to a human without administering pain relief, then pain medication is not given to the animal.”

ULAM technicians are trained in recognizing pain and discomfort in animals. Ringler noted that training is a large part of what ULAM does and one of the most challenging, since new graduate students arrive regularly and must be able to participate in the studies.

A $4 million budget supports animal research facilities, supplies, training and personnel at the U-M.