The University Record, March 15, 1999

By Sally Pobojewski

Health System Public Relations

Interleukin-2, a well-known weapon in the fight against certain types of cancer, has proven to be a powerful new addition to a University of Michigan cancer vaccine that mobilizes the body’s own immune system to attack and destroy malignant cells.

In a study published in the March 2 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), U-M researchers present the results of experiments testing the effectiveness of the vaccine/IL-2 combination on laboratory mice with large, advanced sarcomas or breast cancers. While not included in the PNAS article, U-M scientists also are studying other types of tumors, including aggressive skin cancers called melanomas, to determine their response to the vaccine/IL-2 combination.

It is the first study to combine interleukin-2, a growth factor that stimulates immune system cells to divide and multiply, with a cancer vaccine made from specialized white blood cells called dendritic cells, which alert the body’s immune system to the presence of cancer.

“The addition of IL-2 substantially improved our vaccine’s anti-tumor effect,” says James J. Mule, professor of surgery, director of the Tumor Immunotherapy Program at the Comprehensive Cancer Center and a member of the Life Sciences Commission.

“Some mice with well-established, advanced lung and skin tumors showed no evidence of disease after treatment,” Mule says. “Others experienced substantial tumor regression and lived longer than mice treated with either the vaccine or IL-2 alone.”

Based on these results, the U-M researchers have requested approval to begin a Phase II trial of the cancer vaccine with IL-2 in adults with advanced metastatic melanoma.

Dendritic cells alert the immune system to cancer by presenting pieces of digested tumor proteins called antigens to white blood cells called T-lymphocytes. When the dendritic cell finds a T-lymphocyte with a docking site to match the tumor antigen, the T-cell starts producing messenger chemicals that stimulate production of T-lymphocyte “clones.” All these new T-cells are equipped with the exact receptor needed to immobilize and destroy one type of cancer.

While the U-M’s dendritic cell vaccine alone triggered an immune response against cancer cells, it could not produce antigen-activated T-lymphocytes fast enough to overcome large, well-established tumors, according to Mule.

“IL-2 gives the immune response a boost,” Mule says. “First, dendritic cells find and activate T-cells with the specific receptors we need to fight the tumor. Then IL-2 induces those T-cells to rapidly divide and proliferate.”

The fact that interleukin-2 works at low doses in combination with the U-M cancer vaccine is important, Mule adds, because the toxic effects of high-dose IL-2 therapy have limited its effectiveness against cancer in the past.

“Dosages of IL-2 used in our study were 25 to 50 times lower than the maximum tolerated dosage,” Mule says. “They were comparable to the low dosages used today to stimulate immune response in people with HIV or patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation.”

Significant results from the study include:

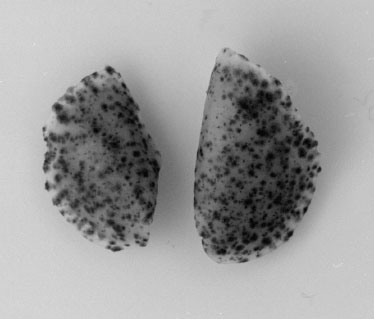

While other researchers are experimenting with tumor vaccines made from single tumor peptides mixed with dendritic cells, Mul and his colleagues use whole tumors called lysates-tumor cells that have been frozen and thawed several times to kill them. “By using the entire tumor cell, we are sensitizing the immune system to attack all the antigens in that tumor, making it less likely that tumor cells will escape detection,” he explains.

In addition to Mule, co-authors on the PNAS study are Koichi Shimizu, research fellow; Ryan C. Fields, who received his undergraduate degree in 1998 and is now attending Duke University Medical School; and Martin Giedlin, associate research director for vaccines and gene therapy research at Chiron Technologies.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Army Research Office, and by gifts from C.J. and E.C. Aschauer and Abbott Laboratories to the Department of Surgery and the Tumor Immunotherapy Program.