The University Record, February 8, 1999

Women in sports still face stereotypes and obstacles

By Diane Swanbrow

News and Information Services

In the week before the Super Bowl, an interdisciplinary panel of scholars met in the Michigan Union to discuss sports and gender—how far we’ve come, how far we have to go, and how we ought to get there. A Community of Scholars Presentation, co-sponsored by the Institute for Research on Women and Gender and the Division of Kinesiology, the discussion began with an historical perspective by panel chair Bruce Watkins, interim director of the Division.

In the week before the Super Bowl, an interdisciplinary panel of scholars met in the Michigan Union to discuss sports and gender—how far we’ve come, how far we have to go, and how we ought to get there. A Community of Scholars Presentation, co-sponsored by the Institute for Research on Women and Gender and the Division of Kinesiology, the discussion began with an historical perspective by panel chair Bruce Watkins, interim director of the Division.

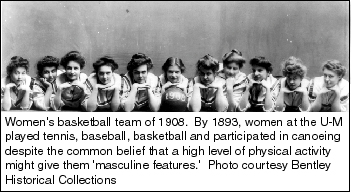

“We should take pride in the fact that sport and athletics were available to U-M students so early,” he said. By 1882, a group of women students had formed “a ladies baseball nine club.” Listed in the yearbook as the team water-carrier was U-M President James B. Angell. By 1884, U-M women were playing tennis and baseball, canoeing on the Huron River, and hiking through the Arboretum. By 1893, they also were playing basketball and had formed a Women’s Athletic Committee.

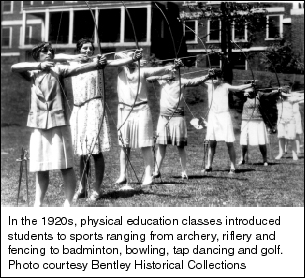

At the same time, Watkins said, women athletes of the past struggled with serious constraints. Among these were cultural views common in the Victorian era that vigorous physical activity presented a danger to women. Many believed it would either damage women physically by making them permanently infertile, or diminish their ability to attract a husband by giving them masculine features. While federal law now mandates equal opportunity for women athletes at the university level, Watkins noted, and some cultural change has taken place within families and communities, many stereotypes and obstacles remain.

“At Smith, where I taught for a while, they took the opposite tack back in the early days,” said psychologist Jacquelynne Eccles. “They were afraid that sitting in class would cause a woman’s sexual organs to atrophy, so they required women to exercise. In the fall, they had ‘Mountain Day,’ in which classes were cancelled and everyone had to go out and hike around. Imagine.”

Eccles, who chairs the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Pathways through Middle Childhood, described some of her findings from a series of large-scale, ongoing, longitudinal studies of children and their parents. By first grade, girls already believe they’re not as good as boys at sports, in general, and at throwing a ball, in particular, Eccles said. They believe they’re better than boys at tumbling and instrumental music, however, and about the same at reading.

Eccles, who chairs the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Pathways through Middle Childhood, described some of her findings from a series of large-scale, ongoing, longitudinal studies of children and their parents. By first grade, girls already believe they’re not as good as boys at sports, in general, and at throwing a ball, in particular, Eccles said. They believe they’re better than boys at tumbling and instrumental music, however, and about the same at reading.

“In fact,” Eccles said, “girls are better than boys at reading. We documented their objective performance in other areas, and found that the variance in the actual performance of young boys and girls was quite small when it came to physical activities.” Eccles and colleagues also asked parents about the talents of sons and daughters, and found that early on, parents believed sons were better at most physical activities than daughters. When explaining why their daughters didn’t do as well, parents were much more likely to say that they didn’t have much talent, but when sons didn’t perform well physically, parents were likely to say they just weren’t working very hard.

Vikki Krane, a visiting scholar from Bowling Green State University, discussed the lesbian experience in sports. Through interviews with 15 lesbian college athletes and 13 lesbian college coaches from around the country—interviews that were not easy to get—Krane found that all 28 had experienced either prejudice and discrimination based on their sexual orientation, or seen these attitudes clearly expressed. She discussed the practice of “negative recruiting,” in which coaches try to dissuade female athletes from attending a rival university through rumors that the coach or team members are lesbians. “The impact of a homo-negative environment on athletes and coaches is enormous,” Krane said. “It creates a great deal of stress, and it erodes self-confidence, motivation and concentration. Ultimately, homophobia and heterosexism are not good for a team’s performance, which, to some people, is the goal of participating in sports.”

Assistant U-M athletics director Warde Manuel wound up the panel presentations by discussing how the U-M is trying to increase opportunities for women athletes without decreasing opportunities for men. A lively discussion followed the presentations, starting with a question for Eccles by psychologist Abigail Stewart. “I’m wondering whether the homophobia that Vikki described may be part of parent’s attitudes about girls and sports,” Stewart said.

“In some ways, it may operate in exactly the opposite way,” said Eccles. “That is, instead of seeing girls as bad at sports because being good might mean they’re lesbians, parents may see boys as good in sports as a way of not seeing them as homosexual. I think parents have a hard time thinking of their young daughters as sexual at all.”