The University Record, December 14, 1998

Why academic medical centers cost more

By Sally Pobojewski

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of three articles describing how the Health System has been affected by fundamental changes taking place in the U.S. health care industry over the past decade. Last week’s article focused on the shift to managed care and the impact it had on the then-named U-M Medical Center in the mid-1990s. This article explains why academic medical centers are particularly vulnerable to the current health care cost squeeze. The final installment, to be published in next week’s Record, will focus on how the Health System is changing and growing, so it can continue to provide the highest quality patient care in spite of continuing reductions in clinical revenue. This series originally appeared in the summer 1998 issue of Michigan Today.

Why is the U-M Health System more expensive than others? One big reason is that it has always been, first and foremost, a teaching institution.

Why is the U-M Health System more expensive than others? One big reason is that it has always been, first and foremost, a teaching institution.

U-M administrators point out that tuition doesn’t begin to cover the costs of training a medical student. Because clinical revenue must subsidize the costs of medical education, they say, teaching hospitals are always more expensive than non-teaching hospitals.

When the first University Hospital opened in 1869, it was the only university-owned teaching hospital in the United States. Its purpose was to provide a clinical practice setting for students at the Medical School, established in 1850. Since 1869, the patient care and educational missions of U-M Hospitals and the Medical School have become so intertwined it is virtually impossible to separate the costs associated with each.

Before managed care, when government agencies and insurance companies were willing to reimburse hospitals on a full fee-for-service basis, it really didn’t matter that part of each patient’s bill went to cover educational expenses.

Before managed care, when government agencies and insurance companies were willing to reimburse hospitals on a full fee-for-service basis, it really didn’t matter that part of each patient’s bill went to cover educational expenses.

Many of today’s managed care companies, however, maintain it’s not their responsibility to subsidize medical education. The HMOs want each academic medical center to document exactly how much it spends on education, so educational costs can be excluded when HMOs set prices for patient care.

A task force of Medical School faculty and administrators is trying to identify the true costs of educating medical students and house officers, which is what the U-M calls residents or new M.D.s, who spend three to eight years specializing in their chosen field. The task force’s job will not be easy.

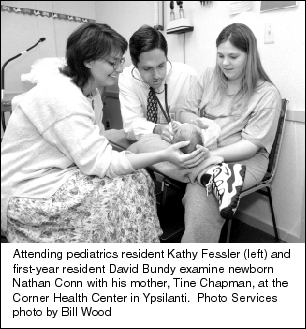

For example, third-year medical students now spend about half their time working with house officers and faculty physicians in 30 outpatient health centers in southeast Michigan. Medical students don’t treat patients, but they do take medical histories and observe patient visits. At the end of the day, how much of the supervising physician’s time was spent on education and how much on patient care? How many more patients could she have seen that day if she hadn’t spent time working with students?

Residents treat patients, but only under the direct supervision of a faculty physician. Even though they never set foot inside a classroom, these physicians spend part of each day on instructional tasks—time which otherwise could be devoted to patient care or research. Also, there are additional demands on nurses who train residents in basic hospital or clinic procedures, and on support staff who handle the extra scheduling and paperwork.

“Teaching in a hospital or clinic setting is not well understood or appreciated by people who are only familiar with teaching in a traditional classroom setting,” says Steven A. Goldstein, a professor of surgery and of biomedical engineering. “It’s intense, one-on-one and requires a major commitment of time and energy.”

Medicare supports residency training

Since its establishment in 1965, the tax-funded federal Medicare program has paid academic medical centers a share of the costs of training the nation’s 102,000 medical residents. Medicare’s share is determined by the percentage of a hospital’s patients who are covered by Medicare.

In 1983, Congress established an additional payment for academic medical centers, called the indirect medical education (IME) payment. IME payments are designed to help teaching hospitals cover the higher costs incurred from treating sicker patients who need more complex and expensive medical care. The exact amount varies from hospital to hospital, because of a complicated adjustment formula written into the Medicare statute.

In 1995, IME payments to academic medical centers totaled $6.1 billion. “IME is the lifeblood of a place like this,” says Rick Bossard, government relations officer for the Health System. Unfortunately, that lifeblood is slowly draining away, as Congress—in an effort to control health care costs and balance the federal budget—keeps reducing the reimbursement amount. When the program started in 1983, the reimbursement rate was nearly 12 percent. The current rate of 7.7 percent will be reduced to 5.5 percent by the year 2001. Since 26 percent of the Health System’s annual gross revenue comes from Medicare, every percentage point drop in IME translates into a multimillion-dollar revenue cut.

And to make life more interesting for the folks in the budget office, all the old fee-for-service payers—Medicare, Medicaid and Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan—are threatening the Health System’s future revenue even more by encouraging members to leave traditional programs and join managed care plans.

More than 25 percent of the Health System’s gross revenue comes from Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan, according to financial director Tom Marks. Just a few years ago, most BC/BSM members were enrolled in traditional, fee-for-service health plans. Today more than 10 percent of all BC/BSM members are enrolled in the Blue Cross HMO, Blue Care Network. Two-thirds of Michigan’s one million Medicaid recipients are in managed care plans now and that number is expected to double within the next few years. And many HMOs in Michigan are offering “senior plans” to encourage people to switch from Medicare to managed care.

As managed care becomes a more dominant force in Michigan, Marks worries about what will happen if the Health System has to compete with less expensive community hospitals on the basis of cost alone.

“So far, most of our major payers have been willing to pay more for basic health care here in order to give their members access to our high-end tertiary care,” Marks says. “The question is: How long will they continue to do this?”

‘Grading’ the hospitals

Just as universities use grade point averages to evaluate applications from potential students, managed care administrators compare hospitals on the basis of cost-per-case. The hospital with the lowest cost-per-case number has a big advantage in the managed care market. The basic premise behind calculating cost-per-case is simple: Add up all your expenses and divide by the number of patients treated in a given period of time.

In practice, it’s not so easy. A complex formula is used to factor in differences in the case-mix ratio between the number of patients admitted, say, for open heart surgery vs. the number going to a clinic to see their primary care physician about a sore throat. Some hospitals include expenses for depreciation, malpractice insurance and even the hospital gift shop. Others limit expenses to direct costs of patient care.

But no matter how you run the numbers, the hard truth is that the U-M Health System is still more expensive than competing hospitals, although not nearly as much as it used to be. James A. Bell, assistant finance director, co-chaired a committee that recently analyzed how UMHS calculates cost-per-case. According to the committee’s report, the re-adjusted cost-per-case calculation for fiscal year 1997 was $7,662. That’s $565 more than the average cost-per-case for comparable academic teaching hospitals in the U.S. and $1,630 more than non-teaching hospitals in southeast Michigan that compete directly with the U-M Health System for patients and managed care dollars.

“If all you do is take total expenses and divide by the total number of patients, of course we’re going to appear more expensive, because the numbers don’t capture the severity of our case mix,” says Gilbert S. Omenn, executive vice president for medical affairs. “Before comparing these numbers, employers, insurers and the media need to look at what they’re paying for. High-risk patients must have access to the specialized treatment we provide, which often is unavailable at other hospitals.”

Transfer patients are expensive

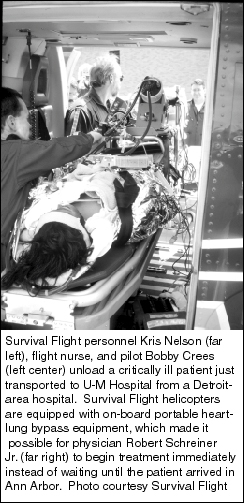

Omenn points out that about 15 percent of admitted patients are transferred from another hospital. Many of these people would die without the advanced treatment technology available at U-M Hospitals and the expertise of its specialists. But intensive care for high-risk patients does not come cheap.

A statistical analysis of nearly 85,000 patients admitted to U-M Hospitals from 1989 to 1993, published in the journal Academic Medicine, shows that transfer patients require longer hospital stays and more expensive care than non-transfer patients.

Patients in C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, for example, come to Ann Arbor from all over the world for Mott’s specialist treatment programs. In a study of children’s hospitals conducted by the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions, Mott was rated almost twice as high as other children’s hospitals on the association’s patient severity index. Patient care costs at Mott raise the cost-per-case calculation for the entire Health System by several hundred dollars per case, according to Omenn.

No one is considering turning away transferred patients or shutting down Mott Children’s Hospital. “We are a state institution and we have a responsibility to care for the state’s children,” says Jean E. Robillard, professor and chair, Department of Pediatrics and Communicable Diseases.

But as the Health System struggles to come up with the money to carry out its responsibilities, the people who balance the budget understand that altruism has its price in the bottom-line world of managed care. Every patient transfer increases the cost-per-case for the Health System, while it reduces the cost-per-case for a competing hospital.

“We are the hospital of last resort,” Bell says. “We treat the sickest, most difficult cases. All our competitors transfer their most difficult and expensive cases to us.”

You can always drop us a line: [email protected].