The University Record, November 2, 1998

Former mob captain gives tough lesson on sports gambling

By Jane R. Elgass

It’s a multi million dollar a year business with strong ties to organized crime that can have a devastating effect on an athlete’s career and ruin a university’s image. And the widespread prevalence of sports-related gambling makes it possible for anyone to become vulnerable to the lure of easy money, from athletes themselves to their friends, families and casual acquaintances.

It’s a multi million dollar a year business with strong ties to organized crime that can have a devastating effect on an athlete’s career and ruin a university’s image. And the widespread prevalence of sports-related gambling makes it possible for anyone to become vulnerable to the lure of easy money, from athletes themselves to their friends, families and casual acquaintances.

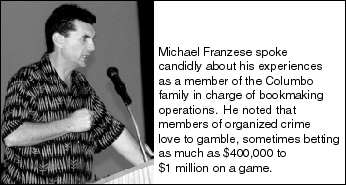

It is all too easy for a gambler to find someone’s weak spot and exploit it, Michael Franzese told audiences in Keen Arena last week. Franzese, a former “captain” for the Columbo organized crime family whose “business” was bookmaking, spoke Oct. 25 to student-athletes from 23 sports and Oct. 26 to Athletic Department coaches and staff.

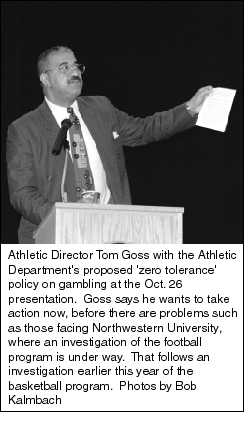

Athletic Director Tom Goss said that the Athletic Department has proposed a “zero tolerance” policy on sports-related gambling.

“Organized crime is all around us and infiltrating college sports,” he said at the Oct. 26 event. The U-M’s football and basketball programs are “highly recognized,” and the soon-to-be presence of casinos in Detroit and the current availability of Internet gambling put the University and its athletic programs at risk of involvement.

Sports gambling involves more than just athletes, Goss noted. It could be a custodian, a friend of an athlete, someone met at a party. “But it’s a serious business because it’s a big business. We want to make sure our student-athletes are aware of the issue and aware of the consequences.

Sports gambling involves more than just athletes, Goss noted. It could be a custodian, a friend of an athlete, someone met at a party. “But it’s a serious business because it’s a big business. We want to make sure our student-athletes are aware of the issue and aware of the consequences.

“We can only educate and make sure that all our athletes and others are aware of the issue,” Goss said. “There will be stiff penalties.”

Goss says he has taken action now, before there are problems such as those facing Northwestern University, where an investigation of the football program is under way. That follows an investigation earlier this year of the basketball program.

The Keen Arena program consisted of a compelling video, narrated by Greg Gumble, on how organized crime can infiltrate a sports program, and Franzese’s presentation.

Franzese, described by introducer Percy Bates as a “man on a mission to protect people from the games they play,” spoke candidly of his involvement in sports bookmaking and drove home the message that everyone involved in collegiate athletics needs to be careful about what they say and to whom.

Bates is professor of education and director, Program for Educational Opportunity, and long-time faculty representative to the Big Ten Conference.

The video, featuring interviews with organized crime members, sports figures and law enforcement officials, pointed out that gamblers hang out where athletes hang out, looking for any tidbit of information—who’s injured, who’s not. Anyone can make money betting based on inside information.

Players are seen by bookmakers as commodities and preyed upon day in and day out. Professional gamblers are very good at disguising their intent, and athletes can be well into relationships with new “friends” before realizing they are in trouble.

“They suck you in before you really realize what’s going on,” one video speaker said. “There will be one little deal and then they will want more and more. Pretty soon you’ll be told, ‘Don’t win by more than nine.’ You can’t get away from them. You’re associated with organized crime and trapped,” he said.

And the targets of big time gamblers need not be high-profile athletes. They can be players who are dissatisfied with their roles or lack of recognition or those who have bad habits that can be exploited, coaches, trainers—anyone associated with the outcome of a game.

“Gamblers become pretty desperate,” the video noted. “There are more criminals out there than athletes and they are very creative.”

Franzese, who was recruited by the FBI to work with professional sports teams near the end of his 10-year prison term for racketeering, said he sees his appearances before college athletes as “an ounce of prevention. I try to inform, educate, put a little fear in them.”

Players may be in control on the court or the field, but when they step over the line to gambling, they are not in control. “They are easy prey and can quickly fall victim to unscrupulous people,” he said. “Colleges use me to demonstrate how serious the problem is,” said Franzese, who, in addition to running bookmaking operations, ran an operation that cheated the federal government out of $14.6 million in gasoline taxes.

“My job is to make kids understand that the video is real,” he said, “not a Hollywood production. Organized crime figures love to gamble. It’s a business for them.

“Don’t be a hot shot. Don’t test yourself. It’s not as harmless as you think.

“Everyone [in bookmaking] is somehow, someway linked with organized crime. The chances are very good that the bettors [who can’t cover their losses] will get a visit from organized crime,” Franzese stated.

“It always turns out bad. You always get caught,” Franzese added. “Bookmakers always are under investigation,” he said, “and they make deals with the government to avoid the charges. They buy their way out,” usually by selling out the athletes. “Your best friend is probably the person who will get you in trouble.”

Does this mean everyone needs to become paranoid? “Yes, a little,” Franzese said. “If someone wants to give you a gift and it stops at that, that’s O.K. But if you meet again, the antenna should go up. It’s not always someone in a black suit and silk tie. You wouldn’t know who I was. You have to be careful who you talk to. Gamblers are very astute. I’ve met athletes through my banker.

“You may think you’re removed from the big city, but you have no concept of how big the gambling network is,” Franzese said. “They come to you. You don’t have to search for them.”

You can always drop us a line: [email protected].