Flipping an egg carton of light traps giant atoms

In an egg carton of laser light, U-M physicists can trap giant Rydberg atoms with up to 90 percent efficiency, an achievement that could advance quantum computing and terahertz imaging, among other applications.

Highly excited Rydberg atoms can be 1,000 times larger than their ground state counterparts. Nearly ionized, they cling to faraway electrons almost beyond their reach. Trapping them efficiently is an important step in realizing their potential, the researchers say.

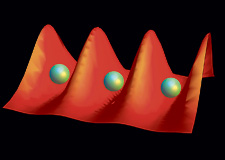

Giant Rydberg atoms become trapped in wells of laser light in a new highly efficient trap developed by U-M physicists. They liken it to an egg carton. Sarah Anderson .

Here’s how they did it:

“Our optical lattice is made from a pair of counter-propagating laser beams and forms a series of wells that can trap the atoms, similar to how an egg carton holds eggs,” says Georg Raithel, a U-M physics professor and co-author of a paper on the work published in the current edition of Physical Review Letters. Other co-authors are physics doctoral student Sarah Anderson and recent doctoral graduate Kelly Younge.

The researchers developed a unique way to solve a problem that had been limiting trapping efficiency to single digit percentages. For Rydberg atoms to be trapped, they first have to be cooled to slow them down. The laser cooling process that accomplishes that tended to leave the atoms at the peaks of what the researchers call the “lattice hills.” The atoms didn’t often stay there.

“To overcome this obstacle, we implemented a method to rapidly invert the lattice after the Rydberg atoms are created at the tops of the hills,” Anderson says. “We apply the lattice inversion before the atoms have time to move away, and they therefore quickly find themselves in the bottoms of the lattice wells, where they are trapped.”

Raithel says there is plenty of technological room left to reach 100 percent trapping efficiency, which is necessary for advanced applications. Rydberg atoms are candidates to implement gates in future quantum computers that have the potential to solve problems too complicated for conventional computers.

— Nicole Casal Moore, News Service

Wealthier nations have more fast food and more obesity

New research from U-M suggests obesity can be seen as one of the unintended side effects of free market policies.

A study of 26 wealthy nations shows that countries with a higher density of fast food restaurants per capita had much higher obesity rates compared to countries with a lower density of fast food restaurants per capita.

“It’s not by chance that countries with the highest obesity rates and fast food restaurants are those in the forefront of market liberalization, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada, versus countries like Japan and Norway, with more regulated and restrictive trade policies,” says Roberto De Vogli, associate professor in the School of Public Health, and lead researcher of the study.

For example, in the United States, researchers reported 7.52 fast food restaurants per 100,000 people, and in Canada they reported 7.43 fast food restaurants per 100,000 people. The paper reported the obesity rates among U.S. men and women were 31.3 percent and 33.2 percent, respectively. The obesity rates for Canadian men and women were 23.2 percent and 22.9 percent, respectively.

Compare that to Japan, with 0.13 fast food restaurants per 100,000 people, and Norway, with 0.19 restaurants per capita. Obesity rates for men and women in Japan were 2.9 percent and 3.3 percent, respectively. In Norway, obesity rates for men and women were 6.4 percent and 5.9 percent, respectively. The relationships remain consistent even when researchers controlled for variables such as income, income inequality, urban areas, motor vehicles and Internet use per capita.

— Laura Bailey, News Service

Teens who view smoking in movies likely to use cigarettes for the first time

Teens who see movie characters using cigarettes are quicker to try smoking than their peers who did not watch the same scene, a new study finds.

However, the exposure to movie images involving cigarettes does not appear to lead teens who have tried smoking to become regular smokers sooner, says Sonya Dal Cin, an assistant professor of communication studies and the study’s lead author.

Having friends who smoke and access to cigarettes at home resulted in teens smoking earlier in life, the study states.

Dal Cin wrote the study with Mike Stoolmiller, a senior research associate at the University of Oregon, and James Sargent, a professor of pediatrics at Dartmouth Medical School.

The researchers investigated the link between the exposure to smoking in movies and how it affects teens.

In four separate interviews, researchers asked the teens if they saw any of 50 randomly selected movies from a comprehensive list of top grossing films. They also obtained background information and inquired about other social influences that might affect whether or not they smoked.

The results showed that age significantly could predict smoking behavior. Gender was not related to the timing of smoking behavior.

Race and ethnicity were associated with how quickly someone who experimented with cigarettes became an established smoker, but did not affect how early they started smoking. A higher household income and better school performance delayed the onset of smoking.

Dal Cin noted that the relation between exposure to movie smoking and teens smoking for the first time is a concern because starting earlier increases the likelihood of becoming heavy smokers.

The findings appear in the Journal of Health Communication.

— Jared Wadley, News Service

Acid rain poses a previously unrecognized threat to Great Lakes sugar maples

The number of sugar maples in Upper Great Lakes forests is likely to decline in coming decades, according to U-M ecologists and their colleagues, due to a previously unrecognized threat from a familiar enemy: acid rain.

Over the past four decades, sugar maple abundance has declined in some regions of the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada, due largely to acidification of calcium-poor granitic soils in response to acid rain.

Sugar maple forests in the Upper Great Lakes region, in contrast, grow in calcium-rich soils. Those soils provide a buffer against soil acidification. So sugar maple forests here have largely been spared the type of damage seen in mature sugar maples of the Northeast.

But now, a U-M-led team of ecologists has uncovered a different and previously unstudied mechanism by which acid rain harms sugar maple seedlings in Upper Great Lakes forests.

The scientists have concluded that excess nitrogen from acid rain slows the microbial decay of dead maple leaves on the forest floor, resulting in a buildup of leaf litter that creates a physical barrier for seedling roots seeking soil nutrients, as well as young leaves trying to poke up through the litter to reach sunlight.

“The thickening of the forest floor has become a physical barrier for seedlings to reach mineral soil or to emerge from the extra litter,” says ecologist Donald Zak, a professor at the School of Natural Resources and Environment and co-author of an article published online Dec. 8 in the Journal of Applied Ecology. Zak also is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

“What we’ve uncovered is a totally different and indirect mechanism by which atmospheric nitrogen deposition can negatively impact sugar maples,” Zak says.

— Jim Erickson, News Service

Do you hear what I hear? Noise exposure surrounds us

Nine out of 10 city dwellers may have enough harmful noise exposure to risk hearing loss, and most of that exposure comes from leisure activities.

Historically, loud workplaces were blamed for harmful noise levels.

But researchers at U-M found that noise from MP3 players and stereo use has eclipsed loud work environments, says Rick Neitzel, assistant professor in the School of Public Health and the Risk Science Center. Robyn Gershon, a professor with the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, University of California, San Francisco is the principal investigator on the study.

This proved true even though MP3 player and stereo listening were just a small fraction of each person’s total annual noise exposure.

Neitzel says he was surprised by the findings. As an occupational hygienist, he expected regular users of trains and buses along with work-related activities to be the chief culprits in excessive noise exposure.

They found that one in 10 transit users had noise exposures exceeding the recommended limits from transit use alone. But when they estimated the total annual exposure from all sources, 90 percent of transit users and 87 percent of nonusers exceeded the recommended limits, primarily due to MP3 and stereo usage.

“That two out of three people get the majority of noise exposure from music is pretty striking,” Neitzel says. “I’ve always viewed the workplace as a primary risk for noise exposure. But this would suggest that just focusing our efforts on the workplace isn’t enough, since there’s lots of noise exposure happening elsewhere.”

— Laura Bailey, News Service

New ‘Flume Room’ contains 150 mini Huron Rivers

More than 3,000 gallons of Huron River water recently were trucked to the U-M campus to create 150 mini-Hurons that are used to study how environmental changes affect freshwater habitats like rivers and streams.

The new $1 million U-M “Flume Room,” the largest facility of its kind in North America. Its 150 miniature streams are used to study how environmental change impacts freshwater habitats like rivers and streams. Photo by Austin Thomason, U-M Photo Services.

The artificial streams are called flumes, and U-M’s new $1 million “Flume Room” is in the basement of the Dana Building, home to the School of Natural Resources and Environment (SNRE). The U-M flume lab is the largest facility of its kind in North America, and possibly the world.

“We’re taking little pieces of the Huron River — the water, the rocks, the bacteria, the algae, the insects and other small invertebrates that inhabit the stream — and we’re placing them into these 150 small flumes. We try to mimic all the river conditions we possibly can,” says Bradley Cardinale, an assistant professor at SNRE and principal investigator of the flume project.

Running an experiment 150 times in 150 identical flumes provides what researchers call high replication, which enables them to precisely estimate how different environmental stresses — such as pollution, species invasions and extinctions, climate change and erosion — affect the river’s health.

“I call it environmental triage,” Cardinale says. “Basically, we’re trying to figure out what forms of environmental change are having the biggest impacts on streams.

“The rationale for doing this is that the world’s rivers and streams are being exposed to all sorts of human-induced stresses, and we can’t possibly address them all — we don’t have enough money, we don’t have enough people and we don’t have enough time,” Cardinale says. “The point of this project is to figure out our top priorities. This project is going to tell us the top stressors we should be focusing on.”

Cardinale also is an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, LSA.

— Jim Erickson, News Service

‘Fingerprinting’ method tracks mercury emissions from coal-fired power plant

For the first time, the chemical “fingerprints” of the element mercury have been used by U-M researchers to directly link environmental pollution to a specific coal-burning power plant.

The primary source of mercury pollution in the atmosphere is coal combustion. The U-M mercury-fingerprinting technique — which has been under development for a decade — provides a tool that will enable researchers to identify specific sources of mercury pollution and determine how much of it is being deposited locally.

“We see a specific, distinct signature to the mercury that’s downwind of the power plant, and we can clearly conclude that mercury from that power plant is being deposited locally,” says Joel Blum, the John D. MacArthur Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

Blum is co-author of a paper published online Dec. 13 in the journal Environmental Science & Technology. The lead author of the paper is U-M doctoral candidate Laura Sherman, who works with Blum.

“This allows us to directly fingerprint and track the mercury that’s coming from a power plant, going into a local lake, and potentially impacting the fish that people are eating,” says Sherman, who has worked on the project for four years.

Effects on humans include damage to the central nervous system, heart and immune system. The developing brains of fetuses and young children are especially vulnerable.

Other authors of the Environmental Science & Technology paper include the late Gerald Keeler, who directed the U-M Air Quality Laboratory; Jason Demers of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences; and Timothy Dvonch, who is the current director of the U-M Air Quality Laboratory.

— Jim Erickson, News Service