By mimicking the structure of the silk moth’s antenna, U-M researchers led the development of a better nanopore — a tiny tunnel-shaped tool that could advance understanding of a class of neurodegenerative diseases that includes Alzheimer’s.

A paper on the work is newly published online in Nature Nanotechnology. This project is headed by Michael Mayer, an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Department of Chemical Engineering. Also collaborating are Jerry Yang, an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, and Jiali Li, an associate professor at the University of Arkansas.

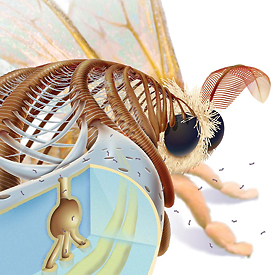

A special coating on the nanotunnels of a silk moth’s antenna is the inspiration for a similar oily layer on synthetic nanopores, tiny measurement devices. Illustration by Chris Burke.

Nanopores — essentially holes drilled in a silicon chip — are miniscule measurement devices that enable the study of single molecules or proteins. Even today’s best nanopores clog easily, so the technology hasn’t been widely adopted in the lab. Improved versions are expected to be major boons for faster, cheaper DNA sequencing and protein analysis.

The team engineered an oily coating that traps and smoothly transports molecules of interest through nanopores. The coating also allows researchers to adjust the size of the pore with close-to-atomic precision.

“What this gives us is an improved tool to characterize biomolecules,” Mayer says. “It allows us to gain understanding about their size, charge, shape, concentration and the speed at which they assemble. This could help us possibly diagnose and understand what is going wrong in a category of neurodegenerative disease that includes Parkinson’s, Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s.”

Mayer’s “fluid lipid bilayer” resembles a coating on the male silk moth’s antenna that helps it smell nearby female moths. The coating catches pheromone molecules in the air and carries them through nanotunnels in the exoskeleton to nerve cells that send a message to the bug’s brain.

One of Mayer’s main research tracks is to study proteins called amyloid-beta peptides that are thought to coagulate into fibers that affect the brain in Alzheimer’s. He is interested in studying the size and shape of these fibers and how they form.

“Existing techniques don’t allow you to monitor the process very well. We wanted to see the clumping of these peptides using nanopores, but every time we tried it, the pores clogged up,” Mayer says. “Then we made this coating, and now our idea works.”

To use nanopores in experiments, researchers position the pore-pricked chip between two chambers of saltwater. They drop the molecules of interest into one of the chambers and send an electric current through the pore. As each molecule or protein passes through the pore, it changes the pore’s electrical resistance. The amount of change observed tells the researchers valuable information about the molecule’s size, electrical charge and shape.

Due to their small footprint and low power requirements, nanopores also could be used to detect biological warfare agents.

A research highlight on this work will appear in an upcoming edition of Nature.