In the middle of a lecture on data structures and algorithms, David Chesney might start telling the students about sailboats — just to shake them from their lecture daze and get them to listen.

“Generally, most of my computer science professors don’t stray too far from computer architecture or code snippets,” says Chelsea LeBlanc, a senior and LSA computer science major from Plymouth, recalling the sailboat story Chesney told the first day of her Data Structures and Algorithms course.

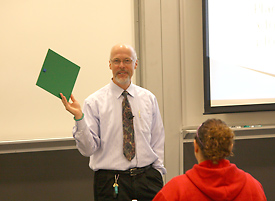

David Chesney, a lecturer in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, says storytelling illustrates important points, helps students remember content and adds variety to a long lecture. Photo by Steve Crang.

“He got the students’ attention,” she says. “And when the stories did relate to the material, it made it that much easier to remember key points in the lecture.”

Storytelling, that traditional staple of the kindergarten or pre-school classroom, isn’t just for the youngest students, say some U-M instructors who are discovering the value of stories to aid college student instruction.

Chesney, a lecturer in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, College of Engineering, says storytelling helps illustrate important points, gives coherent meaning to seemingly divergent topics and helps students remember content. He says stories also break up a long lecture.

“Engineering educators may feel that telling stories is a distraction or divergence to communicating the necessary content of a course. However, it is possible to use story-telling as an improvement to traditional teaching techniques,” he says.

“In end-of-semester evaluations, they always ask for more and say that the stories really added to the class,” Chesney says.

“Hearing stories about a professor’s life and experience turns them from a course audio-track into a real person,” LeBlanc says.

“I’ve never had another professor use storytelling in class. I’ve also never had the core lessons and material of a course stick with me as strongly as they did in that course.”

After a 22-year career at General Motors, Chesney became a lecturer at U-M 12 years ago. The new lecturer first used storytelling as a way to reach students.

“I just started doing it. As students became more and more responsive to it, I thought that maybe I was on to something. So, I started doing a little research on techniques and trying to figure out why it is such a successful technique,” he says. Through research, Chesney collected enough material to produce three papers — one of which won a best paper award — on the subject, which he presented to the American Society for Engineering Education. Among other findings, he offers do’s and don’ts for faculty who want to explore storytelling.

First, Chesney urges sticking to the essentials of stories and avoiding unimportant details. He says to watch students’ reactions to see if the story is engaging them. Avoid stories that are in poor taste, but don’t be afraid, when appropriate, to tell personal stories.

Chesney says while it makes sense to assume that some faculty are more natural storytellers than others, any faculty member can learn to develop the ability.

“I noticed that when I told a story, my students would listen much more closely to what I told them,” says Erik Hildinger, an engineering lecturer who, like Chesney, had a first career before he became a lecturer. A practicing attorney in the Detroit area for about 15 years before teaching, he recalls reading a law text that touted the value of storytelling as a way to convey information to jurors. “It’s actually a technique employed by successful plaintiffs’ attorneys in civil actions,” Hildinger says. While he didn’t use the technique as a lawyer, he does as a lecturer.

“I have the impression that students watch more visual entertainment than we did, even a generation ago,” Hildinger says, adding studies suggest the same. He says storytelling takes advantage of modern students’ receptiveness to visual stimulation, as stories can paint a picture. “I notice too that students seem to recall the stories, and you can refer to them briefly in class to remind them of what you’ve taught,” Hildinger says.

While he does plan stories for particular lectures, “They often come to me on the spot. I often tell of things that have happened to me, but I’ll use any good story,” he says.

Telling a tale

Lecturer David Chesney offers a simple story about courage:

“Part of the reason that I became a college professor is that my Norelco Triple Header broke. Although my day job was as a middle manager in the automotive industry, I taught whenever I could, and realized that teaching was my true passion.

“Back to my Norelco. It broke. Being both frugal and an engineer, I decided to fix it. I went to a local store to purchase the parts and was amazed at how expensive they were. In the same aisle were shaving cream and blade shavers. I am embarrassed to say that I had never blade-shaved by the age of 40. To save money, I decided to try.

“That night after tucking my children into bed, I closed the bathroom door and lathered my face. I was nervous. I emerged from the bathroom 45 minutes later, blood-soaked red tissues hanging from my face. However, I could claim a partial victory because I had learned a new skill.

“One might ask what my shaver has to do with teaching. At the end of that year, I was mentally cataloging my major accomplishments that year. The first was learning how to blade shave. The second was — there was no second major accomplishment. I decided it was time for a change. I soon left my job for a full-time teaching position.

“The lesson: It takes courage and sometimes a little bloodshed to acquire a new skill like storytelling.”