A concrete material developed at U-M can heal itself when it cracks. No human intervention is necessary — just water and carbon dioxide.

A handful of drizzly days would be enough to mend a damaged bridge made of the new substance. Self-healing is possible because the material is designed to bend and crack in narrow hairlines rather than break and split in wide gaps, as traditional concrete behaves.

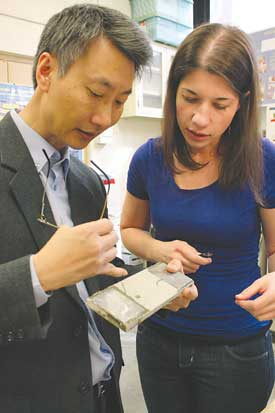

“It’s like if you get a small cut on your hand, your body can heal itself. But if you have a large wound, your body needs help. You might need stitches. We’ve created a material with such tiny crack widths that it takes care of the healing by itself. Even if you overload it, the cracks stay small,” says Victor Li, the E. Benjamin Wylie Collegiate Professor of Civil Engineering and a professor of Materials Science and Engineering.

A paper about the material is published online in Cement and Concrete Research. It will be printed in a forthcoming edition of the journal. The professor says this new substance could make infrastructure safer and more durable.

In Li’s lab, self-healed specimens recovered most if not all of their original strength after researchers subjected them to a 3 percent tensile strain. That means they stretched the specimens to 3 percent beyond their initial size. It’s the equivalent of stretching a 100-foot piece an extra three feet — enough strain to severely deform metal or catastrophically fracture traditional concrete.

“We found, to our happy surprise, that when we load it again after it heals, it behaves just like new, with practically the same stiffness and strength,” Li says. “Self-healing of crack damage recovers any stiffness lost when the material was damaged and returns it to its pristine state. The material can be damaged and still remain safe to load.”

The engineers found that cracks must be kept to less than 150 micrometers, and preferably less than 50, for full healing. To accomplish this, Li and his team improved the bendable engineered cement composite, or ECC, they’ve been developing for the past 15 years.

More flexible than traditional concrete, ECC acts more like metal than glass. Traditional concrete is considered a ceramic. Brittle and rigid, it can suffer catastrophic failure when strained in an earthquake or by routine overuse, Li says. But flexible ECC bends without breaking.

The average crack width in Li’s self-healing concrete is less than 60 micrometers. That’s about half the width of a human hair. His recipe ensures that extra dry cement in the concrete exposed on the crack surfaces can react with water and carbon dioxide to heal and form a thin white scar of calcium carbonate, a strong compound found naturally in seashells.

Today, builders reinforce concrete structures with steel bars to keep cracks as small as possible. But they’re not small enough to heal, so water and deicing salts can penetrate to the steel, causing corrosion that further weakens the structure. Li’s self-healing concrete needs no steel reinforcement to keep crack width tight, so it eliminates corrosion.

By reversing the typical deterioration process, the concrete could reduce the cost and environmental impacts of making new structures. And repairs would last longer. The American Society of Civil Engineers recently gave the country’s roads, bridges, water systems and other infrastructure a “D” grade for health. The federal stimulus package includes more than $100 billion for public works projects.

“Our hope is that when we rebuild our roads and bridges, we do it right, so that this transportation infrastructure does not have to undergo the expensive repair and rebuilding process again in another five to 10 years,” Li says.

Li will give a keynote address on self-healing concrete at the International Conference on Self-Healing Materials in Chicago in June.