Melanoma, deadliest skin cancer, does not fit mode

One of the most promising new ideas about the causes of cancer, known as the cancer stem-cell model, must be reassessed because it is based largely on evidence from a laboratory test that is surprisingly flawed when applied to some cancers, researchers say.

By upgrading the lab test, the scientists showed that melanoma — the deadliest form of skin cancer — does not follow the conventional cancer stem-cell model, as prior reports suggested.

The findings also raise questions about the model’s application to other cancers, says Sean Morrison, director of the Center for Stem Cell Biology at the Life Sciences Institute (LSI).

“I think the cancer stem-cell model will, in the end, hold up for some cancers,” Morrison says. “But other cancers, like melanoma, probably won’t follow a cancer stem-cell model at all. The field will have to be reassessed after more time is spent to optimize the methods used to detect cancer stem cells.”

Results of the research appear in the Dec. 4 issue of Nature.

The cancer stem-cell model steadily has gained supporters over the last decade. It states that a handful of rogue stem cells drive the formation and growth of malignant tumors in many cancers. Proponents of the controversial idea have been pursuing new treatments that target these rare stem cells, instead of trying to kill every cancer cell in a patient’s body.

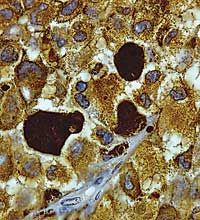

But in a series of experiments involving human melanoma cells transplanted into mice, Morrison’s team found that the tumor-forming cells aren’t rare at all. They’re quite common, in fact, but standard laboratory tests failed to detect most of them.

Scientists previously estimated that only one in 1 million melanoma cells has the ability to run wild, exhibiting the kind of unchecked proliferation that leads to new tumors. These aggressive interlopers are the cancer stem cells, backers of the model say.

But after updating and improving the laboratory tests used to detect these aberrant cells, Morrison’s team determined that at least one-quarter of melanoma cells are “tumorigenic,” meaning they have the ability to form new tumors. The laboratory tests are known as assays.

“The assay on which the field is based misses most of the cancer cells that can proliferate to form tumors,” Morrison says. “Our data suggests that it’s not going to be possible to cure melanoma by targeting a small sub-population of cells.”

Melanoma kills more than 8,000 Americans each year. The human melanoma cells used in the mouse experiments were provided — with the patients’ consent — by a team from the Multidisciplinary Melanoma Program, one of the country’s largest melanoma programs and part of the Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“People were looking to the cancer stem-cell model as an exciting new source for the development of life-saving cures for advanced melanoma,” says Dr. Timothy Johnson, director of the melanoma program and a co-author of the Nature paper. “Unfortunately, our results show that melanoma does not strictly follow this model.

“So we’ll need to redirect our scientific efforts and remain focused on the fundamental biological processes underlying the growth of melanomas in humans,” says Johnson, a cutaneous oncologist. “And as we pursue new treatments for advanced melanoma, we’ll have to consider that a high proportion of cancer cells may need to be killed.”

Co-lead authors of the Nature paper are LSI research fellows Elsa Quintana and Mark Shackleton. In addition to Morrison and Johnson, other U-M co-authors are surgical oncologist Dr. Michael Sabel and dermatopathologist Dr. Douglas Fullen.